At the 55th Venice Biennale, Estonia will be represented by the artist Dénes Farkas, with his project Evident in Advance. The project was developed in collaboration with an international team. The exhibition will open on 1 June and remain open until 24 November 2013. Director of the Kumu Art Museum Anu Liivak has expressed her hope of also hosting the project in the future in Kumu. The current article is based on the press conference held on 18 March in Kumu and on a subsequent interview with the team members.

The Dream Team

The team of the Estonian pavilion, which Dénes Farkas has characterised as Dream Team, consists of the artist himself, the curator Adam Budak, the exhibition architect Markus Miessen, designers from the Zak Group, Zak Kyes and Grégory Ambos, and several linguists and philosophers who have contributed to The Book, which will be produced as a part of the project. The collaboration between Farkas and Budak started about two years ago, when Budak was invited to curate the Tallinn Photomonth exhibition in Kumu and found inspiration in Farkas’s works: “I was very much fascinated by the complexity and intensity of his practice, by the modesty of the artist, and by the worlds he creates and seeks.”

Around a master narrative of Farkas’s works, the project started to accumulate as a series of different stages that proceeded from one another, growing to a remarkably international scale for the Estonian art scene. Subsequently, other members of the team were incorporated based on whose practice would best respond to the ideas and concerns of the project. Markus Miessen explains his reason for collaborating as a challenge that will also enrich his own practice: “It is a very spatial work and I think that there is a lot of interpretive potential in bringing something that is already very spatial in terms of content into the space.” Focusing a lot on communication, Miessen’s practice brings relevant ideas to the project and can be seen as not purely architectural, as we understand it commonly, but rather as artistic. The designers from Zak Group have played an important role in bringing the content provided by Farkas, Budak and Miessen into the book and translating it into the design and visual identity of the project.

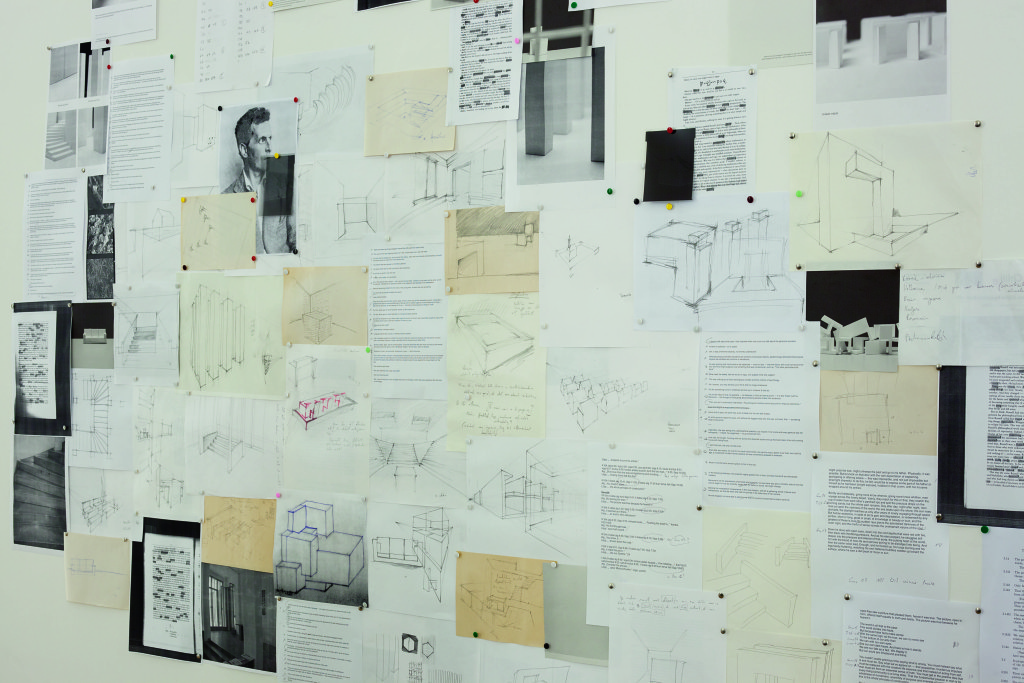

Dénes Farkas. Evident in Advance. 2013. Estonian Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale. Photo: Paul Kuimet

Zeitgeist

When the project was chosen for the Estonian pavilion, the general theme of the biennale had not yet been announced. The fact that the theme of the project corresponds well with Massimiliano Gioni’s Il Palazzo Enciclopedico is merely a coincidence. Nevertheless, there seems to be a certain Zeitgeist that leads to the occurrence of similar ideas, especially considering that this kind of archaeological, interdisciplinary Wunderkammer style of curating has lately also occurred elsewhere, including in documenta 13. As Budak states: “It is something that really corresponds with the current desires to mix art with artefacts that come from other disciplines that are not usually perceived as parts of the contemporary art field.”

In the case of Farkas’ practice, it is possible to talk about a recurring neo-minimalist and neo-conceptualist trend that can be noticed in the local art scene, as well as on a wider international scale. Budak follows up by elaborating on the changes in the art world: “There is a kind of seduction that is going on among young artists to refer to the heroic moments of the 20th century. I think that this could be the moment now to look more profoundly back to the 60s and 70s. This is not only connected to artistic practice but also to curatorial practice. Exhibition formats are being reworked and questioned, especially the Venice Biennale, which is based on national identity.”

National Pavilion

To describe this year’s project, the Estonian Pavilion commissioner Maria Arusoo used the words of Bruce Duffy: it is a kind of intellectual opera. Since the members of this year’s team are from around the world, a lot of meetings are held online or in different locations in Europe. Dénes Farkas is half-Estonian, half-Hungarian, and is based in Tallinn. The Polish-born curator Adam Budak lives in Los Angeles. Markus Miessen lives in Berlin and London. Grégory Ambos and Zak Kyes are based in London. Given all this, one may wonder about its identity as a national pavilion. Is it even justifiable to speak of a national pavilion in the case of such an international team?

It seems that the internationalisation of pavilions is becoming more common in the biennale format. This year, for example, Latvian and Russian pavilions have also invited foreign curators. Perhaps the format of the biennale is indeed undergoing a change in terms of nationality. Maria Arusoo believes that having such an international team gives an artist a new perspective: “This is a chance to get fresh feedback and to see one’s own work in a new light.” Adam Budak has doubts about the importance of nationality in the art scene, saying that identifying oneself with a certain nation has become vague. “It is not important where the artist was born but where the artist is based. In most cases, born in and based in don’t match.”

The World As I Found It

At the beginning of the project, Budak immediately recalled the novel by the American writer Bruce Duffy, The World As I Found It (1987). Bruce Duffy happens to be Budak’s neighbour in Washington, D.C., and Budak took that almost as a sign. The images and installations of the exhibition have been created with the feeling of the book. “Bruce Duffy narrates a magical story, somewhere phantasmagorically suspended in a cloud, the story of the life of the philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein. He was a philosopher of mathematics, of mind, of language, but also a philosopher of colour and a dilettante architect. Wittgenstein built an amazing house on a fjord in Norway, although it was totally dysfunctional and uninhabitable. This corresponds very much with what we want to achieve with the exhibition, which is a maze, a labyrinth of ideas. Ideas that one can actually lose oneself in.”

What Duffy does in the book is pure deconstruction: “The book is written in Wittgensteinian language, and is about performing a kind of surgery, taking things out of one context and putting them into another. Shifting and rehearsing, trying things in different ways and matching elements.” The World As I Found It emphasises the isolation of absence: “There’s no subject because it’s lost and we failed to find it. It’s not that you can enter and see the world as I found it or as he found it, but it’s to trigger or initiate the mechanism in the mind to see it. It is a reconstructed stage, like the rebellious spectacle of language that Duffy creates within the framework of this book.”

Evident in Advance

The philosophical ideas of Wittgenstein as they are presented in Bruce Duffy’s novel have been used as a basis for the project. As Budak explains: “The World as I Found It is about the I, who I am and how I perceive this world. This quest for my identity is very crucial. This kind of I identity is present in Dénes’ seemingly abstract work, which is very much focused on quadrigeneric space, which is absent: there are no human beings in it. It is focused on naked architecture, the under-skin of architecture, how architecture is perceived by our eyes. In this sense, you could say it is biographical, the story of life.” The title of the project, Evident in Advance is based on one of the most crucial notions in Wittgenstein’s philosophy: his perception of the world was based on a priori propositions that are evident.

The philosophical nature of Farkas’s works corresponds well with the way the world is perceived in Bruce Duffy’s novel. The content of the book is translated, reworked, deconstructed and placed into the context of Farkas’s works, composing the narrative of the exhibition. Budak has characterised the world that is created as follows: “The word ‘dream’ is a keyword to enter the world of Dénes Farkas, a world that is out of focus a little bit. A world that is black and white, with shades of grey. A world that is imperfect, imprecise and extremely poetic and theatrical. The book by Bruce Duffy brings in the complexity between what is real and what is fiction, what is truth and what is fake, and it can be applied to the world which Farkas creates.” The project is connected to Farkas’s earlier practice but the dispersal of a singular artist position that comes from working with a team has definitely influenced the artist, who has previously only worked alone. The project includes additional experimental elements that open up his practice from a new perspective, creating some surprises and unexpected twists.

Exhibition Space

This year the Estonian Pavilion is presented in a new environment, in another rented apartment in the Palazzo Malipiero. As the entrance of the apartment is virtually next door to the Palazzo Grassi, it is more exposed and approachable than previous locations.

The exhibition site was chosen before the project had begun. Therefore, the nature of the site determined the way the project was set up. The master plan was inspired by the surroundings, the rose garden and the residential nature of the site. Budak believes that the domestic nature of the apartment gives a unique feeling to the whole project: “It is not a public space, as in the usual pavilion, but a private one. We find this to be positive since it creates a certain intimacy. Dénes’s work is about psychological interior space; the idea is to enter into the artist’s mind.”

The curator continues to describe the process of working with predetermined spatial surroundings: “For Wittgenstein it was a language game; we deal with the exhibition as a game because it is a certain maze: there is a winding hallway and there are four rooms that are like chambers, where you can enter into chapters, as in a book.” Farkas adds that these are rooms where we normally encounter texts: an archive, a classroom, a library and a home. “Reading is a very intimate activity because it’s just me and the world that is inside the book, which is a whole world, but there is nothing in between. I’m into it with my eyes and mind and ability to read. So this is the most intimate space possible.”

Budak finds it inspiring to work with spaces that are not regular, neutral white cubes or museums. As he says: “In the apartment, there are the memories of all those other lives and you cannot escape this. You cannot pretend, for example, that this dining room is not a dining room.” It will be fascinating to see what effect the domestic environment will have on the project as a whole. This influence may be difficult to pin down before the project has finally materialised, even by the artists themselves.

In addition to having chosen an unconventional site, the project has another twist: it intentionally aims to confuse. Budak remarks that the biennale is very much focused on spectacular projects. “We want to try to create a situation that is very confusing. And in this case the piece of work is a study of confusion. We trust the viewer to be courageous enough to take this confusion as something that is a friendly gesture rather than an annoying gesture of being lost in this world.” Given the nature of the biennale, one may of course wonder whether a visitor, having struggled through numerous exhibitions, will have any energy left to really focus on this study of confusion.

Dénes Farkas. Evident in Advance. 2013. Estonian Pavilion at the 55th Venice Biennale. Photo: Paul Kuimet

The Book

The Book, designed by Grégory Ambos and Zak Kyes, and published by the reputable Sternberg Press will form part of the exhibition. The two designers from the Zak Group are also in charge of creating a visual identity for the Estonian pavilion. Ambos sees The Book as more than just a documentation of the exhibition: “It is a kind of expanded space, an experimentation of space. The idea is to confront the images created by Dénes.”

The Book, which reflects Ambos’s and Kyes’s practice, will include a number of essays and texts by various authors. There will be a brand new text by Bruce Duffy and an essay by Daniele Monticelli, who is an Italian philosopher of language. Daniele and Dénes have discussed the project a lot so it is an on-going relationship and collaboration. Plus there will be an essay by the Vienna-based philosopher and linguist Martin Prinzhorn, and an essay by Markus Miessen on the philosophy of the exhibition design and architecture. Also The Book will include two essential reference texts: ‘The Absence of the Book’, a very famous essay by the French philosopher Maurice Blanchot, and ‘Once Desired to Tell the Story’, by the Italian feminist philosopher Adriana Cavarero.

Dénes Farkas (1974), has received an MA in photography from the Estonian Academy of Arts. His post- conceptual photobased practice engineers the substructures of society at the moment it renews and remakes its identity. In 2013 his project Evident in Advance, (curated by Adam Budak) represents Estonia at the 55th Venice Biennale.