Endel Kõks (1912 Tartu, Estonia – 1983 Örebro, Sweden) could be called a most presentable exile Estonian artist, however silly the word combination might seem. Firstly for being represented so well. His collections cannot compete with the legacy of Eduard Wiiralt and Karin Luts that have arrived in Estonia, but compared with many others who left their homeland during WW II, the number of Kõks’s works (also produced abroad) in Estonian private collections and museums is relatively large. In connection with celebrating the artist’s 100th anniversary at the Tartu Art Museum (With Bravery, Freedom and Joy, 14 November 2012–24 March 2013), even more arrived. Also, his rediscovery started already during the Soviet era. The first exhibition took place at the Tartu Art Museum in 1968, including a small selection of pictures made in exile. The 1988 Tartu exhibition relied on the collections of Kõks’s sister Maimu Soidla and focused entirely on the exile period, including developments of Cubism, influences of pop art and abstractions. Therefore, despite the first encounter with some of his paintings, the exhibition as a whole was not a total discovery; it was more like a walk down Memory Lane.

Secondly, Kõks was an enthusiastic organiser-writer, who knew exactly what the mechanisms were that would help an artist make it into art history. Already in 1951, when summarising the art life of Estonians in Germany (where he himself lived from 1944 to 1950), he noted: “The number of sales and the foreign art criticism prove that our artists have what it takes to establish themselves internationally. It is only natural that the best of their works are being purchased by solvent foreigners and will thus be lost to Estonian art, remaining ‘art made by Estonians’. It is crucial that Estonian organisations and institutions establish a collection or collections of art created in exile. From there, these works of art could find their way back to free Estonia.” Later in Sweden, he indeed initiated a project of documenting and collecting exile Estonian art through the Corporation of Estonian Culture. It is a different matter as to how credible the scenario of Estonia becoming free actually was at the time. In practice, this initiative failed, although a small uneven database and picture collection appeared, and today the archive has indeed reached Estonia, whereas the Museum of Estonians Abroad is being enthusiastically founded in Toronto. In addition, a dozen banana crates arrived here in 2012 containing the personal archive of the artist, which clearly proved that, besides his wider mission of mapping the Estonian exile art life, Kõks did not forget to thoroughly document his own life.

All this would have been rather insignificant if Kõks had not left an essential mark in Estonian art history before leaving the country. Despite his youth, he managed to raise high expectations about his future contribution to the development of Estonian art. His talent and singularity were noticed already at the very first public display of his work, in 1938 in Tallinn at an exhibition organised by the Board of the Endowment, two years before graduation from the Pallas Art School. When he finished his studies, he was 28. However, compared with such record-holders as the ‘latecomer’ Ellinor Aiki, who received her diploma at the age of 43, or Karl Pärsimägi, who was on the school list from 1921 to 1937, Kõks was quite young. By the way, the influence of Pärsimägi is quite clear in Kõks’s pictures. He provided a kind of short-cut to French art, which Kõks managed to see directly only at the French art exhibition in 1939 in the Tallinn Art Hall.

Fantasies born out of broken hopes, to a certain extent, also formed the basis of the jubilee exhibition. The press release promised to compare the work of the ‘international man’ Kõks with the work of Elmar Kits and Lepo Mikko, two artists who stayed at home and once belonged to the ‘Tartu trio’. Not every exile artist evokes art-historical fantasies about ‘what would have happened if …’. The display did not quite manage to present a convincing form for these comparisons, but an exciting topic was raised. This made one ponder the crazy undertaking of moulding the Pallas graduates into Soviet artists. In any case, looking at Kõks’s early 1940s picture collection, it is not easy to imagine him painting in the Soviet Estonia of the 1950s. And it is not just due to his avant-garde nature. A proof for that, for example, could be found in the article Fragments of Tartu Profile by Kõks, published in 1962 in the magazine Tulimuld. Here a conversation between three anonymous artists is presented. Of the three, one was assumed to be Kõks’s voice, announcing his credo: “I would like to paint nature as it more or less is, but still with a twist. If you look at nature with open eyes, you see such effects there that no artist has seen before.” The question deals with the artist’s position in general, which was blind to social topics.

The majority of Kõks’s Tartu period work, produced during the Soviet and German occupations, is made up of studio and home pictures, with women, either vainly dressed or being nude; there are also still lifes, urban views and of course café scenes. In the context of Estonian art, Kõks indeed produced a remarkable number of café pictures; the earliest are amazingly modern considering the tranquil mainstream of the Pallas school in the late 1930s. Even in 1943, when he was dispatched in an official capacity to German and Austrian labour service camps, which incidentally was his only trip abroad from Estonia, he returned with idyllic pictures of cafes and leisure activities. Also quite a long section in the article mentioned above was devoted to the special atmosphere of cafes, and their importance as centres of intellectual life in Tartu, where essential conversations, exchanges of information, disputes and even exhibitions took place. However, except for the painting showing lively partying by Pallas artists, in Kõks’s café pictures the passionate human relationships of the intelligentsia of the time are replaced by colour relations in interior details or tense dialogues between the patterns of the ladies’ costumes and the café’s curtain fabrics. If any human contacts are depicted in these generally strikingly autistic café situations, they are invariably reduced to, for example, a picture in a mirror, or they are clearly less significant than communication between objects. For instance, there is a view of a locale with dancing people, where, regardless of the bodily closeness of couples, the most striking relationship is going on between three bright blue cocktail glasses and the blue dress of a dancing woman, which together with a leg in a light stocking looks like an enlargement of an upside-down goblet with a straw.

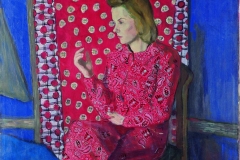

The fact that human beings – although clearly dominant in Kõks’s paintings – are elements of composition rather or something to keep the colour blotches together is also evident in portraits and nudes. For example the Pallas graduation work Gypsy Girl Astra enabled the artist to produce no less than four surfaces with differing decorative ornaments on a bright orange background via the girl. The manner in which he presented the portrait of his sister Maimu, in a red kidney-patterned dressing gown against a bright red background in two different patterns, shocked even such an experienced art critic as Hanno Kompus, who confessed he was lost for words in describing the painting. Over time, Kõks’s abrupt colour sense faded, but a weakness for different decorative fabrics pursued him until the end of his Estonia period. True, not in all his nudes have the powerful pattern-games managed to override the eroticism of bare female bodies, but no woman has made it into a picture without vivid, striped, dotted, floral or lacy fabrics. Some smaller sketch-like paintings are especially indifferent towards the human body; there, the artist has abandoned the traditional impression of depth to the extent that the naked women in their flat stiffness almost seem glued to the pictures. Hence, comparisons with Matisse have frequently been made in analysing Kõks’s work.

Still, there is a small exceptional work among Kõks’s paintings, quite a curiosity, on the topic of the 1905 revolution, which hints at the possibility of a seemingly improbable switch-over. Here, too, the eye is first caught by rare colour combinations, especially the sudden juxtaposition of the greenish-blue and bright red of the clothes of a man in the foreground. The composition’s exalted dynamics, based on diagonals and the militant expressions on people’s faces, reveal the artist’s hidden potential to step out of the idyllic world of women. Alas, the training of socialist realism, and especially the campaign to break all Pallas traditions, which took a truly brutal form in the late 1940s, would not have left even the red on red of this most wondrous of colourists.