Let’s call him Juhan. That is possible and necessary, as well as following Estonian Law regarding personal data. Possible because it is possible, and necessary because those who knew him and who probably loved him might not want the real name of the protagonist revealed in this story. Here, at the very start, we encounter the first problem, the first furcation of the path of this discourse: why? On the one hand, the story is intimate and quite miserable. On the other hand, people still cannot be certain of their own safety when it comes to discussing homosexuality, and even less certain about the safety of the memory of a person deceased long ago. The stigma remains even now.

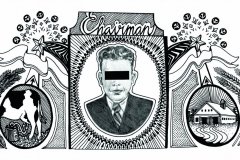

Jaanus Samma’s project Not Suited For Work: A Chairman’s Tale, which represented Estonia at the 56th Venice Biennale of contemporary art in 2015, is based on a story about a person not remarkable in any respect. ‘Juhan Ojaste’ was born in 1921 in an Estonian village, made it through the war, married, worked on a collective farm and eventually became its chairman. Everything was fine until the early 1960s, when he was arrested for same-sex relations. The situation was utterly straight-forward: a long-time lover, an incidental lover and some money involved; he was sent to jail not for the money but for the sheer fact of his homosexuality. He was sentenced to a year and a half, and was released from prison totally broken. He could no longer dream of continuing as the chairman of the farm. His wife abandoned him. His dignity was crushed. He was left with nothing else but doing odd jobs and making equally odd contacts with outcasts like himself. For a quarter of a century more, he lived in the ‘grey zone’ of the homosexual community, and even found a niche for himself; in the late 1980s he ran an underground video club for gays, and in 1990 he was murdered in a conflict over ownership of that covert business. The killer was rumoured to have been a young male prostitute: another victim and another monstrous product of the Soviet system, which criminalized homosexuality. Jaanus Samma’s project does not mention if the killer was ever found; if he was, he has received his victim’s baton in the monstrous marathon of discrimination.

The project Not Suited For Work: A Chairman’s Tale, presented in the Palazzo Malipiero in Venice, is a thorough, scrupulous, pathology-style research on the 1964 ‘Juhan Ojaste’ case. It is designed to be intentionally dry: in the first room, viewers are presented with volumes of criminal records on the case: official references of the defendants, witnesses’ objective statements, expert examinations by psychiatrists and proctologists, investigation records, and the final sentence. Sitting by a table lamp, as in a library or police office, you leaf through copied pages of the criminal case. In the next room, in glass display cases, you see the material evidence: worn-out leather gloves (it seemed to be the loss of gloves that started the conflict between Juhan and his one-night lover, which gave rise to the criminal case), three rubles and fifty kopeks, which Juhan, according to the evidence, promised to pay for sex with the stray acquaintance, and a tube of Vaseline. Another glass case displays what that cost Juhan: the Communist party membership book which he had to return, a wedding ring that was left after his wife fled in horror, and the medal of a war hero: i.e. the whole life of a Soviet man. The third glass case contains urological and proctological instruments of forensic experts, instruments of ultimate humiliation: among the most terrifying and disgusting pages of the criminal case are forensic records listing in detail the length and diameter of the genitals of the individuals under investigation, characteristic features of their sphincters, and conclusions of whether the person in question practiced homosexual acts in active or passive roles. The human body itself becomes evidence against the man himself: yes he could, no there was no anatomical impediment found for this, but some found for that. The expert records the dimensions of the defendant’s penis in centimetres and, dryly and impartially, concludes what prohibited acts the dimensions allowed and what not. Two rooms away, the protagonist in the video will take off his pants and, smearing his penis in black ink, will roll it over a police card usually used for collecting fingerprints: his very body and its natural sexuality are now instrument of crime, the corpus delicti and proof of guilt.

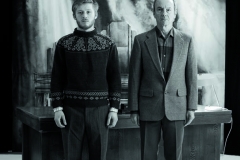

Three videos (two as a pair exhibited on opposite walls, and one demonstrated in a separate room) are completely connected with this compelling, awful criminal story; they do not offer any rethinking or way out of it. Moreover, they re-enact the scenes from the criminal case thoroughly and obsessively, like a nightmare: how they met, where they went, what he touched and what he asked. How he was subsequently arrested, examined by forensic experts, interrogated, humiliated, mixed with dirt, his humanity ripped away. The scenes repeat again and again, locking the viewer in a closed airless space of a story without a single gleam of joy or hope either in the beginning or the end or even in the central erotic scenes: sex is also suppressed here, stigmatized in advance, does not contain a second of enjoyment, not a morsel of naturalness; the only thing it is full of is the feeling of overwhelming guilt, and its only result is humiliation in the investigator’s office. The bed is not a place for love but a site for a crime which goes on and on, and the only way out of this closed circle is through the court docket, then to jail, and then what remains of a man will forever be cast aside.

The only breakthrough to some other dimension is the tiny ‘secret’ room, where there’s nothing to be seen. A small opera box should have a view of the stage, but there is darkness instead. Sitting on armchairs upholstered in red velvet, viewers become listeners: from the darkness, a male voice sings to them; the aria in English is all about anxiety, unrest, struggles with fears and desires, and the presentiment of trouble. But its very beauty and its integration in the paradigm of classical music lift the scene above pain and humiliation or a crime story and transfer it to a space of sublime drama, where evidence and records matter no more, and where it is no more the investigator, defendant and witnesses who argue but life and peril, the presentiment of terror and the craving for rescue. We cannot see them, and there is no stage: we only hear voices. We need characters no more, as the feeling has come to life. At the same time, this of course suggests the commonplaces of USSR’s gay subculture: ‘hidden’ gay men often used opera theatres as places for their discreet dates, and no matter what was to be seen on the stage, the couples performed the play of their lives, their feelings and loves visible to them alone. They were ‘invisible men’ – exactly like Jaanus Samma’s heroes. Exactly like ‘Juhan’. The moment he became visible, he was crushed.

Jaanus Samma does not flatter his hero, and does not write a sugary sentimental story of love oppressed. His plot contains many disgusting elements. His protagonist is not only forced to conceal his sexuality, but also practices random sex in public toilets, ‘picks up’ soldiers for 3.50 rubles per night of love (the sum pedantically recorded in criminal records), and when he has a steady relationship, the promiscuity already engrained in both partners’ skins and turned into a lifestyle of quarrels and jealousy finally brings them to the attention of the police. The Chairman, the war veteran Juhan – homosexual and random sex fancier – is not the least likable, but evokes acute pity. It’s hard to sympathize with a person who feels up young guys in public toilets, but the feeling that this is not how it should be is apparent. Innocent people should not hide in corners, like rats, should not replace the freedom of feelings with shameful couplings for 3.50, and should not build their private lives on the basis of guilt, sin and criminal prosecution.

Samma has chosen the stylistics of alternative history, pseudo-documentalism, though it’s not actually alternative since all the content of the story is real and officially recorded. The artist tries, first, to build a story based upon the materials of the criminal case and, second, to present it as impartially as possible. He even avoids calling his protagonist by name: it is only mentioned in criminal records, and in all other parts of the project he is just called the Chairman. The actors in the videos look completely average, faces you would never remember if you saw them in the street. This makes Samma close to the neo-documentalists, primarily German, such as Thomas Ruff and Thomas Struth: like them, he diligently removes all emotion from the frame; like them, he prefers direct demonstration to storytelling; and, like them, he tries to keep a straight face; but, like them, it is obvious that the seeming documentalism of the image is a deliberate attempt to conceal inner tension which makes it force its way even more strongly to the surface. This makes it all the more fearful: it’s clear that the almost nameless and almost faceless Chairman is not just one unlucky defendant in a criminal case: there are hundreds of other identical broken lives. This criminal case is just an awful symbol of hundreds of other similar cases all over Estonia, all over the USSR, all over the world.

Samma chooses a very ‘Estonian’ manner: unhurried, reserved, devoid of bright colours and loud sounds. Europe, when ‘Nordic design’ is mentioned, immediately pictures spare straight lines and natural materials; thus, Samma’s presentation in the Estonian pavilion at the Venice biennale can be considered a safe strategy of fitting into the ‘national spirit’, which presupposes no jerky movements. But Samma’s deliberate minimalism is also the restraint of a pathologist who does not flinch or turn away when he sees another corpse. The corpse here is the life of a living man, a life which was erased for no reason many years before the unhappy Chairman himself died. The artist’s merit is that he does not present the story of his character as heroic: Juhan is not only not an LGBT advocate or fighter who suffered for his convictions, he is also a miserable person who was placed under such conditions that he could not be anything but miserable. He is the direct result of a repressive system, and it is clear why in this project he has almost no name and almost no face: the name and the face can at any moment be replaced with others, and anyone else would be doomed to the same terrible and pathetic fate. In his shoes, you would look no better nor act more heroic. You would have no way out either, and no artist would be able to make, from your life story, anything more spectacular and attractive than a video about paid sex in some stranger’s flat, lost Party membership and a tube of Vaseline. ‘Juhan’ is not one person but a collective grave of thousands of ordinary people – not heroes, not activists – whose lives were smashed into shards just for the sheer fact of being born who they were. Whose lives were sealed with a stamp: NOT SUITED FOR WORK. Meaning – NOT SUITED FOR LIFE.