I

MURAL LEE

Flicking through reviews of Raul Meel’s works, the usage of the word myth strikes the eye: self-myth, creation of myth, artist’s myth, world myth. Raul Meel is therefore someone whose work as an artist can be compared with myths, and it fits into the framework of myth creation. Raul Meel’s life has not been easy, establishing a career as an artist has been a struggle, his biography contains both triumphs as well as failures, as befits a hero, and the creative path has not been straight, but constantly searching and presumably occasionally also uncertain. Still, all’s well that ends well and, looking around at the current grand and wonderful retrospective in the big hall of the KUMU art museum, we can say that this is a myth with a happy ending.

Myths with happy endings are known as fairy tales. Vladimir Propp’s classic treatment Morphology of the Folktale (orig. 1928) states that the unchanging elements of fairy tales are the functions of characters, which despite varied circumstances are essentially stable. Propp lists a total of 31 functions, and while they may not all appear in the same story, the sequence of functions is always the same. The later structuralist narratology, including Juri Lotman’s analysis of the structure of an artistic text, largely rests on Propp’s legacy. The central idea is that the plot starts with the crossing of borders. The tale begins when a character leaves his or her determined place and crosses the threshold of his existing world into another, unknown and miraculous world. This kind of character will become a hero. The hero’s path is not easy; he not only has to face new dangers in the world beyond the borders but, what’s worse, the act of border crossing makes him a stranger to the people back home. He is no longer recognised. The hero might thus be left wandering for a long time between the two worlds, without inheriting the fairy tale half of a kingdom or being able to return home.

Raul Meel’s myth has two interconnected plot lines.

First, Raul Meel has a degree in electrical engineering. In another society, this might not have been a noteworthy drawback, but in the small and more closed Soviet Estonia, with its semi-totalitarian social organisation, Raul Meel was not seen as an artist. Artists came from the State Art Institute and belonged to the Artists’ Association. Not Raul Meel. The fact that he moved from the army of engineers of the Scientific-Technical Revolution straight into the forefront of the artistic avant-garde constituted a serious disciplinary border violation. This was not supposed to happen. Nevertheless, he decided to take this step.

II

REAL MULE

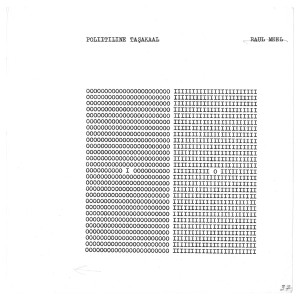

Raul Meel. Political Balance. Typewriter drawing from the unpublished manuscript of concrete poetry Club (Klubi). 1968–1969.

If you are planning to set off on a journey that will include illegally crossing a border, how do you prepare? The key word is suitable gear. Everything you carry must be as compact as possible and multifunctional, quickly assembled and taken apart. Simple and durable. Convertible and easily concealed. Excellent examples here are a fairy tale table that sets itself, a Swiss army knife, a sleeping bag, a bomb belt or cocaine-filled condoms. Or a typewriter’s mono-spaced font.

The first works which Raul Meel managed to get across the disciplinary border at the end of the 1960s and successfully carry into the art world were typewriter drawings.

Whoever has worked in various media knows that text is a very economical medium. Producing texts requires minimal resources and the final product is highly compact (spread James Joyce’s collected works on the floor and they will cover the area of a small Pollock painting). Using a mono-spaced font with equal letter width makes the text extremely durable: as the space is the same for all phonemes, the bits of text can easily be replaced and rearranged without shattering the text’s compact structure. The only aspect that would still make the text rigid and clumsy is narrative. With acute foresight, Raul Meel left it out. The semantic unit of his typewriter drawings had the length of a morpheme or a word, less frequently of a phrase, and full sentences occur very seldom. Compositions made up of bits of text or single characters were enthusiastically received in the Estonian avant-garde art of the 1960s-70s. So, miraculously, the engineer became an artist.

Unable, however, to firmly establish himself in the art world for several decades (until 1987 to be precise), Meel oscillated between the two worlds, working as an engineer at the Design Institute and actively participating in art life. Constant shifting between the two worlds was certainly quite stressful, but also quite profitable, allowing Raul Meel to foster both his intellectual and material independence. Besides, such cross-border to-ing and fro-ing provided him with useful experience, until Raul Meel finally managed to smuggle entire engineering manuals into the art field. This, however, was just the beginning.

Raul Meel’s other act of mythical proportions was that he successfully got his art through the Iron Curtain.

Soviet Estonia was a significant centre of illegal transit. Besides considerable amounts of heroin, art with the highest avant-garde content produced in the Soviet Union crossed the borders of the Estonian SSR and moved on to the capitalist West. The Western world was quite keen on this sort of art, although the Soviet border guards were on the alert: earlier, avant-garde artists used to send their work to the West by post, but controls were tightened in the 1970s and graphic art could be despatched abroad only with a special permit. Under such conditions, very few managed to get their work across borders. According to a legend, there was an open-minded official in Soviet Estonia who helped to register artworks as ordinary letters. Whether or not this person actually existed, a large number of envelopes containing the best Soviet avant-garde art passed through customs and arrived in the West. Alas, this happy situation did not last long. Something shrewder had to be invented.

Raul Meel. Dialogues with Infinity. Exhibition view. Kumu Art Museum, 2014. Exhibition design by Raul Kalvo and Helen Oja.

Raul Meel associated with the local authority on art, Tõnis Vint, through whom he developed contacts with the Moscow underground art world. Meel found friends in the group centred on Ülo Sooster, an Estonian artist living in Moscow and, as a result, he met one of the most influential underground artists in Moscow, Juri Kabakov. The network of Soviet underground art concentrated in the metropolis had some highly functional contacts with Western dealers, and Raul Meel was able to take advantage of these new opportunities. He probably relied on his practical engineer’s mind, as well as his earlier experience acquired in the course of many border crossings between the world of art and engineering.

Understandably, only the most compactly packaged avant-garde art was able to slip through the ever more impenetrable Iron Curtain: series-based, minimalist, abstract and conceptual. Raul Meel’s most brilliant invention of this type is his print series Under the Sky, started in the 1970s. Theoretically, the series contains 5328 prints, all of which can be described as variations on a one-line formula. A huge work that could be transported completely invisibly, or as Raul Meel himself recalls: “inside me, in my head, in my heart” (conversation with Andres Kurg, 2014). You could walk calmly across the border, have the customs people carry out a thorough search, and all the while you have six thousand prints in your heart.

A few prints from the series reached West Germany, where they received second prize at the Frechen Print Triennial in 1974. This achievement can be seen as the realisation of Raul Meel’s second heroic deed, an even more miraculous border crossing.

III

RULE MALE

There were failures as well: Raul Meel’s deals with the Sao Paolo Biennial, MoMA and Flash Art were all foiled by the Soviet authorities. Still, deeds were done, the plot was sound and in the longer perspective it was no longer possible to divert the course of the myth. What was now supposed to happen, happened.

According to Vladimir Propp, the finale of a fairy tale shows the hero being recognised, and the hero then ascends to the throne. Indeed, in the late 1980s Raul Meel was finally recognised at home. Official recognition followed, and he was elevated to the status of a classic. Raul Meel took his seat on his well-earned throne.

Through Raul Meel’s works of the last few decades – ritual fire installations, his artist’s book Solomon’s Song of Songs and others – the public has been addressed by a new archetype, different from the earlier hero: a priest-king.

That, however, is another story.

Raul Meel, DIALOGUES WITH INFINITY

Kumu Art Museum, 9 May – 12 October 2014

It is difficult to use anything but superlatives about this exhibition.

A brilliant artist – Raul Meel – check. Confident curatorial effort – Eha Komissarov and Raivo Kelomees – check. Perfect exhibition design – Raul Kalvo and Helen Oja – check. A beautiful catalogue – designer Tuuli Aule – together with a number of enjoyable essays – Eha Komissarov, Raivo Kelomees, Virve Sarapik and others – check. A whole that is bigger than the sum of the above-listed parts – check.

My personal wow!-experience occurred while reading Eha Komissarov’s text in the catalogue, which suddenly introduced me to the link between the 20th century avant-garde and the exhibition design of metal framework. I at once headed back to the exhibition to have another look.

Raul Meel (1941), Estonian graphic artist, painter, sculptor, installation artist, concrete poet, fire performance artist, beekeeper. He represents the radical wing of the Estonian avant-garde art in the 1970s–1980s.