There is nothing more complicated than following the call of those who research Eastern European art space to focus on similarities, coincidences and differences from a broader, regional perspective. Unity often turns out to be the fruit of imagination, although the researchers of post-World War II art innovation in the Baltic countries might now hope for a unifying link that supports art treatments regardless of ethnicity.

In 2007, Visvaldis Ziediņš, a local artist and bohemian, died in the Latvian seaside town of Liepaja. Since 1964, he had been working as a set designer at a Liepaja theatre and decorated the shop windows in town. To some extent, Ziediņš participated in Liepaja’s art life without ever attracting wider attention. There were no traces of posthumous fame for some time. His legacy – ca 3000 works and an extensive archive – was unsuccessfully offered to the Latvian Art Museum and it was saved from destruction thanks to the initiative of the commercial gallery Galerija 21, which purchased the collection at a low price and decided to examine it properly. The art historian Ieva Kalniņa did the research. In 2012 she presented Ziediņš’s work, together with a catalogue, in the Arsenal exhibition hall in Riga. In 2014 the KUMU Art Museum organised the same exhibition, and in 2015 it will travel to the USA.

Ieva Kalniņa has compared the emergence of Ziediņš’s legacy to a cosmetic operation on the art history façade of the Soviet period, which avoided any changes, and she has forced art institutions for the first time to consider artists who did not represent the official art world.

Latvia is thus faced with the issue of accepting the first consistently non-formal artist and trying to find a place for him in Latvian national art history, whereas for Estonia Ziedinš offers numerous fascinating points of comparison. The structure of non-formal art in Soviet Estonia was infinitely more elaborate, and the number of artists who could be classified as non-formal was considerable. Anti-Soviet art experiments moved through Estonia in waves, from the 1950s-1960s every emerging generation added something that could be seen as opposing Soviet art, and thus various trends characterising Western art innovations played out here. There was naturally quite a bit of confusion in Estonia in determining who was a non-formal artist. If it were based on whether an artist belonged to a creative union or not, there would have been only one serious non-formal artist in Soviet Estonia: Raul Meel, who as an avant-gardist was not accepted into any unions. As Ziedinš started in the 1950s, his work can be associated with the Tartu abstractionists of the same period, whose wish to institutionalise their collage experiments led to a great deal of criticism. The next stage in Ziediņš’s development, when he moved towards assemblage and object art, has points of contact with the first attempts in pop and op art, represented in the late 1960s by the group Visarid, which operated at Tartu University under the supervision of Kaljo Põllu.

Compared with Estonia’s narrowly specialised art experiments, Ziedinš seems like a Latvian titan, and in his provincial solitude he managed to create an impressive number of original works. These are characterised by stylised figures, paintings inspired by abstractionism, and objects in the collage and ready-made techniques. Unfortunately for him, not one art trend in post-WW II Latvia supported this abundant flood of imagination. It is not easy to tackle this kind of phenomenon in any art history or explain how Ziedinš could have been so totally ignored and left to his own devices. After all, Latvia was not a Russian oblast, where a non-formal artist had to hide from the authorities.

We are linked with Ziediņš by independent experiments in abstract art, surrealism and pop-art, where difficulties in trying to describe such attempts inevitably arise. If we are talking about completely replacing established cultural signs with new ones, they cannot generally be described without running into contradictions. It is therefore easiest to tackle Soviet art outside the official canon as a purely political discourse and ignore the aesthetic side. Consistent politicising often causes conflicts with the artists’ own aspirations, confirmed by the unwillingness of Estonian, and more broadly all Soviet, women artists to associate their work with feminism. Non-formal art, whose emergence and development offer exciting material and are firmly connected with ideological opposition and dissidence, constitutes a total meta-phenomenon as an artefact. Non-formal art is an inconsistent structure, referring to almost all art phenomena standing outside the ruling cultural norm. Unfortunately, it is dealt with by systems that shun contradictions, for example art history, with its hierarchic structure, which only amplifies the incompleteness of the non-formal art structure.

Art innovation ceases to be a problem when an image of a maverick or barmy artist is sneaked into its structure, as probably happened in Liepaja with Ziediņš. The work of a maverick does not evoke complaints about poor plastic thinking or lack of sensitivity in colour treatment. Since Boris Groys, the entire non-conformist art of the 1950s–1960s has been suspected of either imitating the West or lacking aesthetic competence. I would not be quite so harsh. Instead, I prefer to find a way to evaluate realisation reduced to the zero level, or objects made of local materials. How to be prepared for the fact that non-formal art always leads outside definitions?

In the Baltic countries, the province participated in non-official art for a long period of time. It is increasingly difficult to understand this in Estonia; in his crazy biography, Ziediņš in Latvia proved that it was perfectly feasible to cultivate non-official art over the course of 30 years if public attention were avoided. A local artist is a contradictory figure and has complicated relations with his environment. Connected with the activities of the local community, he is subjected to processes which deal with the identity development and myth creation of the local area. The local artist becomes synonymous with the critical artist when he takes an oppositional approach1.

The attitude of Ziediņš towards the Latvian art canon of the time was so critical that, after graduating from the Department of Decorative Design of the Liepaja School of Applied Art in 1964, he saw no point in continuing at the Academy of Art. Instead of the academy, Ziediņš began to cultivate his imagination and acquire esoteric knowledge. “I am experiencing a great crisis. I find myself between the constructed and the existing world. In the existing world, there’s a lot that’s not acceptable (any longer), and the constructed world is disrupted through contact with the existing one. Probably. If someone were listening to me talking about it (which I haven’t done), they’d regard me as mad.”

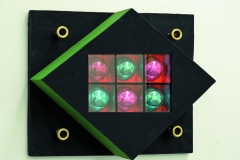

The artist was thus forced to make do without any supporting structures and like-minded people. He kept a diary instead, where he interpreted his own work throughout the years. The authentic self-descriptions of this independent artist could well fill a gap in the non-formal art of the Baltic region. Unfortunately, no contemporary culture discourse takes seriously this brilliant artist who invented his entire body of work by himself. Critical art history, influenced by post-structuralism, fights against over-emphasising the romantic myth of the artist and the role of intuition, even when the actual practice contradicts the theory of the “artist’s death”. Ziediņš, who had no serious contacts with Western art, constructed his art universe from what was available, emphasised the importance of intuition and supported himself in every possible manner, for example by quoting in his diaries the later ideas of Tolstoi about the special status of the artist. To put art innovation into practice, Ziediņš went through the necessary purification stages, which led him to a bubbling diversity of art language. He absorbed the topics of the religious beyond and the universe, and tackled issues of the relationship between allegory and symbols.

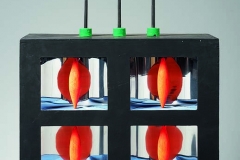

There is a secret unity of ideas between Ziediņš and the first Estonian op and pop art cultivator Kaljo Põllu, although expressed in totally different ways. Both worked with found objects and produced unique pieces of art out of mass culture residue. As was common with their generation, they expanded, in full seriousness, the boundaries of op and pop art. Faithful to the materials acquired from everyday surroundings that had no meaning as symbols, the artists produced compositions which ignited the interpretation process and thus created new associations and meanings. The 1960 generation only acknowledged art that led to assessment. This method, of course, had no success when artists influenced by the neo-avant-garde, such as Tõnis Vint and Raul Meel, began working with the concept of the empty room and began to appreciate the formal sides of a composition. The cheerful tradition of making art by gathering objects and making something out of them ended in Estonia in 1970. Põllu indeed afterwards focused on researching the mythological world of the Finno-Ugric boreal wing. Ziediņš had no competitors in Latvia and so could carry on, becoming immersed in primitive animism and magic, where his objects acquired totem-like features.

1 In 1990 S. Rapoport tackled, in the context of Lithuania, the sociological profile of an artist operating in the provinces, focusing on establishing the negative features of provincialism. See Рапопорт Сергей Самуилович, “”Синдром провинциальности” творческой интеллигенции“, http://www.gumer.info/bibliotek_Buks/Culture/Article/Rap_Sindr.php

2 Entry of 20.02.1965 in Diary No.22 of Visvaldis Ziediņš. Ieva Kulakova (Kalnina). Movement. Visvaldis Ziediņš. 2012, Galerija 21, p. 154.