Estonia’s first appearance at a World’s Fair came in Paris in 1937, in the form of a joint pavilion with Latvia and Lithuania. Both at the architecture competition and later in the busy furnishing phase, the designers strove to define their national representation strategies and to present their national visual identities to the rest of the world.

World’s Fairs have always been places for experimental and imaginative architecture. Being a component of the modern culture of the market economy, the most famous works from World’s Fairs – London’s Crystal Palace, the Eiffel Tower, Le Corbusier’s Pavillon de L’Esprit Nouveau and 33 years later his office’s Philips pavilion, the Atomium in Brussels and others – have been signal accomplishments in modern architecture. The function of the pavilions is to create surprise and make a visual splash, combining distinct national elements with universally recognisable keywords of the modern world, such as tourism, technology, manufacturing and consumption. How something is shown is more important than what is being shown.

Estonia’s joint Baltic appearance in Paris came at a time when cultural and economic ties between the three countries were even closer than they are now and, although there was initial hesitation (at least in Estonia), the decision in favor of a joint pavilion probably stemmed from budgetary considerations. In line with the theme of the fair, Art and Technology in Modern Life, the pavilion had to be modern to the core, i.e. realized in a Functionalist style, using geometrical and simple forms, a style that by that time had secured a strong foothold, particularly in the architectures of private homes in Estonia.

The conditions for the pavilion design competition stated clearly that the external architecture had to be as neutral as possible and not incorporate nationalist features.[i] It is possible that in the end the finished pavilion was too neutral: it contrasted sharply with the originality of Alvar Aalto’s Finnish pavilion, which boldly staked out, at the international level, his vision of plasticity and “living wood”. The Baltic pavilion had also to be of wood, with approximately 1,000 m2 of exhibition space.

In the summer of 1936, a winner was unanimously picked from among 10 projects – the project of Aleksander Nürnberg of Estonia (receiving a prize of 3,000 French francs) – with honorable mention going to Visvaldis Paegle (Riga), Jonas Kovalskis (Kaunas) and Erich Jacoby (Tallinn). Nürnberg (1890–1964) was a Pärnu-based architect of Baltic-German origin. Typical of his generation, he had been educated at the Riga Polytechnic Institute: the Baltic connection was truly strong back then. The Paris pavilion represents a conspicuously modernist outlier in his oeuvre of otherwise Pärnu-centred conservative buildings. In that same year, 1936, competitions were also held for the design of the foyer, to be furnished jointly by the Baltics, and for the sculpture that would grace the middle of the foyer. As a result, the general design of the building was assigned to Oskar Raunam, a 22-year-old Estonian and recent graduate of the State School of Arts and Crafts in Tallinn. Three sculptors were picked: Ernst Jõesaar (Estonia), Gotlibs Kanpes (Latvia), and Juozas Mikėnas (Lithuania).

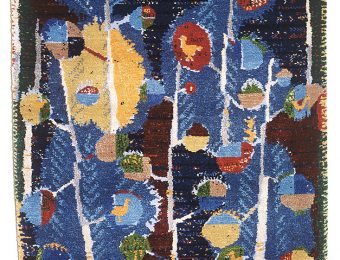

The official opening of the pavilion was in June 1937. At the event, the Lithuanian Prime Minister delivered the opening address. After just five months, in the early winter of the same year, the pavilion was demolished. In total, the construction cost exactly a million francs, and three-fourths of this was paid by the French. At the exhibition, lavish prizes were doled out to all 52 participating countries, and the Estonians also brought home numerous grand prizes, honorary diplomas, and gold, silver, and bronze medals. Among other grand prix winners were the architect Nürnberg, Oskar Raunam, Eduard Taska, Voldemar Mellik and the Kodukäsitöö (Home Handicrafts) limited company. The entire exhibition was in fact largely structured around handicrafts and applied art: both original art and modernized folk art seemed suitable to develop the country’s national image in the international arena. Technology – which today’s Estonia uses to promote itself – was less developed back then and unspoiled nature had not yet entered people’s consciousness as valuable in its own right.

The pavilion had an extremely simple design and layout: a square-shaped footprint where the central foyer was surrounded by halls devoted to each of the three countries and the fourth unoccupied side was completely made of glass. The main foyer was dark green and had plywood cladding (the sponsor was the well-known A. M. Luther plywood factory in Tallinn) and one wall was covered by a mural painting by Oskar Raunam dedicated to six themes: animal husbandry, fishing, forestry, farming, the song festival, and midsummer celebration. Each country chose the interior decoration scheme for its hall. The Estonian one was wide-ranging, featuring paintings, applied art and lace sheets, a radio unit produced in Estonia, sports trophies, and even a relief with a portrait of President Konstantin Päts. Incidentally, the press criticized the exhibition for being sparse and one-dimensional: critics called the surfeit of applied art works overkill for audiences who had already seen similar things in other pavilions. The modern furniture designed by Richard Wunderlich, one of the first and most prominent Estonian professional interior designers, is worth mentioning, as it fit in well with the Functionalist architecture of the pavilion. The building itself was considered too neutral and lacking in character; critics said it should be the first and last joint pavilion experiment, as the personality of each individual country was lost in the mix.

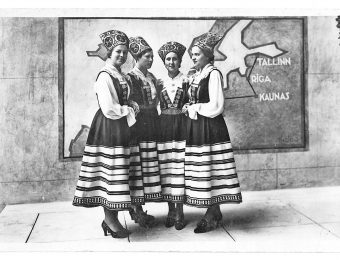

More broadly, the process of construction and furnishing the pavilion provided fodder for interesting discussions on nationalism, strategies for national representation and image building: the desire to rise above the fray of a Made in Estonia commercial fair full of bric-a-brac to a more minimalist, selective solution. The four Estonian folk costume-clad young women who served as guides and became celebrities through the many interviews they did upon returning to Estonia proved to be particular attractions at the pavilion. Unlike today’s unifying global village, where stressing “nationalism” and national boundaries has long ceased to be salient, these concepts had much more patriotic significance back in the 1930s and they were served to the people in a rather outré form. Yet, as the renowned Estonian architect Edgar Johan Kuusik presciently observed after seeing the exhibition in Paris, while such a major exhibition would not be complete without a commercial bazaar selling Estonian merchandise, “a fair should be limited to the fair, and the demonstration of art and technology should be conceived in a more distinguished context. Is it in fact symbolic of our times that we can no longer distinguish the real and authentic from the ersatz, which, bedecked in gaudy garb, shouts over everything else, magnetically attracting the masses and simultaneously trampling, mocking and titillating them, as is and always will be the case with the masses?”[ii]

[i] Materials on the competition can be found in the National Archives of Estonia (RA), ERA.957.14.361; the history of the construction has been treated thoroughly by I. Solomõkova – see Eesti kunstikontaktid läbi sajandite [Estonian art relations over the centuries]. Vol. 2, Tallinn: Eesti Teaduste Akadeemia, 1991.

[ii] Unpublished manuscript, seeRA, ERA.957.14.73.