At the end of 1999, young painters practising figural painting began to emerge in Estonia. They compensated for their often limp style with imaginative visions, built upon unsuitable and questionable images. Although by the year 2002 it has become clear that they should be left alone to develop their style, and that they represent much more than peripheral attempts at rebellion stemming from the counter-culture, the number of admirers of the new figural painting is small.

This trend sells neither at home nor on the international arena, and it should strictly be treated as the personal art adventure of the authors. John Smith (this alias hides painters Marko Mäetamm and Kaido Ole) has mentioned that the road of a brave adventurer takes him to labyrinths full of crazy adventures and mazes of unimaginable spiritual dimensions. ‘Adventure’ is here, probably, synonymous with ‘freedom’, a word that was clearly exploited in the post-socialist art scene and has gradually been left out of the discourse. In other words, freedom pinned us to the floor rather than releasing us. Although this is not its aim, art that transcends norms diagnoses the times. The new figural painting, although it is accused of irony, excellently reflects the inner confusion of Estonian painting and the stressful changes in the local art context.

neither at home nor on the international arena, and it should strictly be treated as the personal art adventure of the authors. John Smith (this alias hides painters Marko Mäetamm and Kaido Ole) has mentioned that the road of a brave adventurer takes him to labyrinths full of crazy adventures and mazes of unimaginable spiritual dimensions. ‘Adventure’ is here, probably, synonymous with ‘freedom’, a word that was clearly exploited in the post-socialist art scene and has gradually been left out of the discourse. In other words, freedom pinned us to the floor rather than releasing us. Although this is not its aim, art that transcends norms diagnoses the times. The new figural painting, although it is accused of irony, excellently reflects the inner confusion of Estonian painting and the stressful changes in the local art context.

The problem of our art, and a constant source of conflicts, lies in reality and in questions related to the reflection of this reality. Art should engage in subjects such as politics, business and sex, which draw together the energy of society, but remain, because of their social nature, unreachable for the art of painting, which is constructed within aesthetic parameters. The fact that painting has to face such subjects is a problem in need of a solution. Most probably this is one of the greatest traumas in the history of Estonian art. Lively discussions have been held in Estonia about ugliness, violence and stupidity as condemnable problems of art; right now the problem has acquired a somewhat unpleasant political taste.

The problem of our art, and a constant source of conflicts, lies in reality and in questions related to the reflection of this reality. Art should engage in subjects such as politics, business and sex, which draw together the energy of society, but remain, because of their social nature, unreachable for the art of painting, which is constructed within aesthetic parameters. The fact that painting has to face such subjects is a problem in need of a solution. Most probably this is one of the greatest traumas in the history of Estonian art. Lively discussions have been held in Estonia about ugliness, violence and stupidity as condemnable problems of art; right now the problem has acquired a somewhat unpleasant political taste.

At present, while we are tearing ourselves away from the wretchedness of the post-communist era, society expects different, much brighter mirrors to shed idealised and unambiguous light on our reality. Estonia has reached the point of craving and searching for a positive image. When politicians talk about Estonia, they convey a positive vision of social progress, symbolised by the success of the liberal market economy and unprecedented reforms. The world of art also makes attempts to interpret optimism on the basis of a new correlation of forces, aligning with the art taste of the new bourgeoisie and economic activities of the art market. The result has been surprising, allowing the old art of the Soviet years to gain a new lease on life as a status symbol and the carrier of our artistic identity.

Ten years ago, when the greatest changes in our society were just beginning, and when it was impossible to predict or review anything, the idea that our fetishist vision of art should be based on the art originating from our previous world would have been outrageous. Naturally, this is a compliment to the creators of this art – the generations of talented artists of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s – who were able to concentrate despite the situation at those times and to discuss our identity with sufficient depth. The severity and melancholy of the figural painting of that time not only expresses a joyless and oppressed way of thinking; it is well equipped to represent a construction of a much wider scope. Intellectualising one’s emotions and subjecting internal feelings and conflicts to the control of reason has given rise to an extremely competitive aspect of identity, which is considered to be national identity in the new times as well. Consequently, we may sail from our Soviet true home to search for our Nordic roots, and then we can even proceed to Europe.

Ten years ago, when the greatest changes in our society were just beginning, and when it was impossible to predict or review anything, the idea that our fetishist vision of art should be based on the art originating from our previous world would have been outrageous. Naturally, this is a compliment to the creators of this art – the generations of talented artists of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s – who were able to concentrate despite the situation at those times and to discuss our identity with sufficient depth. The severity and melancholy of the figural painting of that time not only expresses a joyless and oppressed way of thinking; it is well equipped to represent a construction of a much wider scope. Intellectualising one’s emotions and subjecting internal feelings and conflicts to the control of reason has given rise to an extremely competitive aspect of identity, which is considered to be national identity in the new times as well. Consequently, we may sail from our Soviet true home to search for our Nordic roots, and then we can even proceed to Europe.

Classical works are accessible, understandable and sell more easily.

In some wider context our recovered art image may prove necessary: we may learn the skills of stoic resistance and ways of remaining decent human beings. Many people use these models even now to survive in an era of great changes. Here we should mainly deal with the problem of conformity, which cannot explain all events in the art of a transitional society.

Russian cultural philosopher A. Nedel believes that the degeneration of ontological structure, which has occurred in post-totalitarian societies, requires the discovery of a new reality, where the fight for survival can be compared to the fight for presence. The artist’s fight for his presence and for the establishment of his autonomy is related to the emergence of an arbitrarily subjective author. An individual, with his experience, emotions and desires, is positioned against such a background. Such an impressive expression of the artist’s self can be found in no other period in Estonian art but the 1990s. All relations in all spheres of life become especially intense in a period of drastic changes, and reality is opposed to self-image, but no general and regulating categories can be found anywhere, and the artist, being aware of the instability of his output, deconstructs his discourse in order to establish his autonomy.

can be compared to the fight for presence. The artist’s fight for his presence and for the establishment of his autonomy is related to the emergence of an arbitrarily subjective author. An individual, with his experience, emotions and desires, is positioned against such a background. Such an impressive expression of the artist’s self can be found in no other period in Estonian art but the 1990s. All relations in all spheres of life become especially intense in a period of drastic changes, and reality is opposed to self-image, but no general and regulating categories can be found anywhere, and the artist, being aware of the instability of his output, deconstructs his discourse in order to establish his autonomy.

The author’s self has traditionally been marginal in Estonian art, and it has been impossible to exhibit it in an outstanding and narcissistic way. Only the video art of the 1990s displays the appearance of necessary requisites for the emergence of subject. Here the artist’s strategies are directly aimed at the affected examining of the artist’s ‘self’, and related to the dramatisation of conflicts of a person who participates in the symbolisation process. Self-image is expressed in an exceptionally powerful way and directed towards the author also because of the fact that the artist is very often the only performer in his video – he carries out the performance. In the art of painting, subjectivity must be related to other ideologies. For instance, a painter has to be ready for instances in which the media starts to shape the content of his work and to interpret the painting in an exactly opposite way from the idea the artist had in mind.

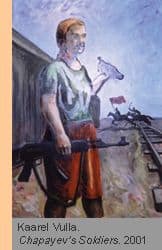

Kaarel Vulla and Priit Pajos disregard requirements of form and ignore the opportunities to use different colours in their works. For the general public they are simply awkward bunglers. We can follow the aspirations of figural art by following the rearrangement of imaginary stresses in the use of the verb ‘to be’. The word acquires a pronouncedly present-related meaning, which frees the artist’s ‘being’ from earlier existential meanings and helps him to integrate into the signs and symbols which originate from a transformed society. The Soviet period would not have been able even to generate such signs and symbols. The origin of new signs is not always clear, and cannot often be explained by artistic influences. The artist’s individuality is inherent and reflects externality, not vice versa. It synthesises international art language and local aspects that are fundamental from the viewpoint of nationality. Unusualness and violence of environment are opposed to the ego, subjecting it to the fragments of historical memory.

Kaarel Vulla and Priit Pajos disregard requirements of form and ignore the opportunities to use different colours in their works. For the general public they are simply awkward bunglers. We can follow the aspirations of figural art by following the rearrangement of imaginary stresses in the use of the verb ‘to be’. The word acquires a pronouncedly present-related meaning, which frees the artist’s ‘being’ from earlier existential meanings and helps him to integrate into the signs and symbols which originate from a transformed society. The Soviet period would not have been able even to generate such signs and symbols. The origin of new signs is not always clear, and cannot often be explained by artistic influences. The artist’s individuality is inherent and reflects externality, not vice versa. It synthesises international art language and local aspects that are fundamental from the viewpoint of nationality. Unusualness and violence of environment are opposed to the ego, subjecting it to the fragments of historical memory.

Russian cultural critic S. Kuznetsov recommends discussing mass culture and pop culture separately in the territory of the former Soviet Union. The former has roots, it is aimed at wide masses of people, it is nearer to folklore and stylisation and, differing from the West, it is surrounded by a positive semantic meaning. Pop culture is clearly a product of the present time; it feeds on show business, the glamour of the media and aggressive marketing strategies. It occupies the foremost place in the list of preferences of the new economic elite. The new Estonian figural painting can equally be applied to both of these cultures, meaning that its stylistic distinctions and subjects depend on which sphere is socially closer to the artist.

mass culture and pop culture separately in the territory of the former Soviet Union. The former has roots, it is aimed at wide masses of people, it is nearer to folklore and stylisation and, differing from the West, it is surrounded by a positive semantic meaning. Pop culture is clearly a product of the present time; it feeds on show business, the glamour of the media and aggressive marketing strategies. It occupies the foremost place in the list of preferences of the new economic elite. The new Estonian figural painting can equally be applied to both of these cultures, meaning that its stylistic distinctions and subjects depend on which sphere is socially closer to the artist.

Such division can be discussed as an opposition between authentic eccentricity and glamour in the provinces. Such interpretation is offered by Donald Kuspit, who searches for an alternative to postmodernist art, which is based upon simulacra. Provincial art is governed by the infantile, psychopathology and parapsychological experience. It is figural, but without concrete form, because it is born of improvisation, of personal expression and of narcissistic satisfaction, spiced with illusions of glamour. If we search for non-alienated art, we can find it only in the provinces. It is opposed by the narcissistic satisfaction and hedonism of glamorous art.

The critical potential of the new figural art should not be overestimated, since its main opponent and discussion partner is a purely aesthetic subject, the limits of the painting of Soviet origin. The real explosive is hidden in the basis of the art – in the material used by the artist, meaning the discourses of the tabloid culture. On one hand, it is good that some reflections of the madness of the world can be found in the small territory of the painting. But on the other hand, in cases where the artist completely exhausts his subjects, the problem of moral responsibility immediately arises. Decisions are not made by exhibition juries any more, but by committees fighting pornography. Never before has the conflict between freedom and responsibility been as urgent in Estonian art as it is now.

There are plenty of questions; for instance, what attitude should be taken towards art featuring pornography or psychedelia in an era when moral, sexual and psychedelic emancipation has caused insoluble social problems in Estonia? Should the critic discuss the participation of art in the circle of such subjects or not? We can state that in the 21st century, the question of the limits of art has lost its purely aesthetic content in Estonia as well.

Artists

Kaarel Vulla, graduated from the Department of Art at the University of Tartu.

Kaarel Vulla’s painting The Funeral of the Mobile Phone, full of pathos, gives a good example of how very different social discourses can revolve around some cult object and thus be addressed. The situation is extremely crazy, but complicated as well, since it turns out that funerals and the ritualisation of death are desecrated in the work. Vulla’s method is a matter of using the simple effect of the parable, borrowed from surrealism.

since it turns out that funerals and the ritualisation of death are desecrated in the work. Vulla’s method is a matter of using the simple effect of the parable, borrowed from surrealism.

Mass scenes full of figures, populist attitude and an anecdotal method of presenting the story refer to the model of Stalinist social realism, but at the same time, they are deconstructed using hints of the supernatural. Vulla is a fan of science fiction, but he treats the subject in an entirely unconventional way. In Vulla’s paintings we cannot find the virtual impersonal perfection familiar in sci-fi films, which are full of technological chauvinism. Instead of the world of Star Wars, the mythology of which is still unreachable for Vulla’s generation, we can see a reflection of the earlier mythology of UFOs, called by C. G. Jung the only real mythology of the new era and the only chance to meet the supernatural. The artist treats his subject as a childish adventure story, disturbing its linearity with crazy flights of fancy. It is impossible to observe the fullness of the unfolding action, but the painting is vigorous and full of spirit. The people in the painting are so primitive that the world of humans seems to be more supernatural than the world of aliens.

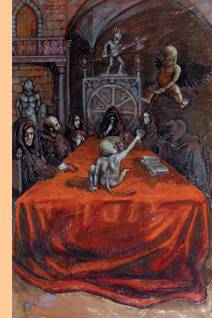

Priit Pajos, The Department of Art at the University of Tartu.

Pajos’s painting is characterised by narrow, impenetrable dark space and brownish colours, which would  be well suited for a trap or for enacting a tragedy. The spectator feels deep anxiety and uneasiness. The people in the picture are in shock or in a state of affect; they meet fantastical beings, or become free of their causal relations. The artist shows the vision of an individual, picturing a universal all-embracing experience, and complementing the traditional opposition of the sensual/intellectual with brutal intonations of morbidity, bestiality and prurience. Religious motifs are important for the artist, and although Pajos stands outside of established religions, we see from the rhetoric of his paintings that he is well aware of them. The depiction of death and the violence of death occupy a central position in his work; it is further developed into a breaking of taboos and defiling of sacredness. In the painting Hauarüvetaja (A Grave Desecrator), grief develops into the denial of the violence of death. The man who urinates on a grave is painted as a deeply tragic person, offering, as a father figure, a number of ways of interpretation. Pajos’s method of constructing allegorical discourse upon hallucinations, and his use of affect, make his work a precedent in which fantasy is tightly interwoven with problems of psychoanalysis.

be well suited for a trap or for enacting a tragedy. The spectator feels deep anxiety and uneasiness. The people in the picture are in shock or in a state of affect; they meet fantastical beings, or become free of their causal relations. The artist shows the vision of an individual, picturing a universal all-embracing experience, and complementing the traditional opposition of the sensual/intellectual with brutal intonations of morbidity, bestiality and prurience. Religious motifs are important for the artist, and although Pajos stands outside of established religions, we see from the rhetoric of his paintings that he is well aware of them. The depiction of death and the violence of death occupy a central position in his work; it is further developed into a breaking of taboos and defiling of sacredness. In the painting Hauarüvetaja (A Grave Desecrator), grief develops into the denial of the violence of death. The man who urinates on a grave is painted as a deeply tragic person, offering, as a father figure, a number of ways of interpretation. Pajos’s method of constructing allegorical discourse upon hallucinations, and his use of affect, make his work a precedent in which fantasy is tightly interwoven with problems of psychoanalysis.

KIWA, Estonian Academy of Arts (not graduated)

Kiwa discusses advertising and the media in an uncompromisingly cynical way and manipulates the media-shaped façade of society in his pop-paintings. Usually, art that is based on media images creates glamorous illusions of the narcissistic satisfaction of society. Kiwa throws sand into the well-oiled machinery of glamorous discourse by discussing pornography, especially child pornography. The explosion and rich business of pornography are subjects that many Eastern European artists treat as the breaking of taboos and the widening of the boundaries of art. Kiwa, who paints seductive small girls similar to images found in porno shops, is also of the opinion that taboos manifest pathology and neuroses, which people unsuccessfully try to repress; nevertheless, by doing so they still emphasise the hypocrisy of political correctness and the self-destructive mechanisms of democracy.

cynical way and manipulates the media-shaped façade of society in his pop-paintings. Usually, art that is based on media images creates glamorous illusions of the narcissistic satisfaction of society. Kiwa throws sand into the well-oiled machinery of glamorous discourse by discussing pornography, especially child pornography. The explosion and rich business of pornography are subjects that many Eastern European artists treat as the breaking of taboos and the widening of the boundaries of art. Kiwa, who paints seductive small girls similar to images found in porno shops, is also of the opinion that taboos manifest pathology and neuroses, which people unsuccessfully try to repress; nevertheless, by doing so they still emphasise the hypocrisy of political correctness and the self-destructive mechanisms of democracy.

John Smith

Kaido Ole, Estonian Academy of Arts

Marko Mäetamm, Estonian Academy of Arts

John Smith is an alias. He mocks the production principles of modern business firms. John Smith has been created to generate and produce a well-functioning and extremely modern product; it contains shared roles and  positions; it proceeds only from the economic character of the product; it is always in time and in the right place; it uses modern colours, invests in espionage, and never does anything out of some internal urge or simply to fill time. Smith’s product is made immediately after the arrival of an order. It exists, like a parasite, only due to the already existing. He defines his effortless actions as jokes. His art is characterised by enchanting technical virtuosity, disinformation, craziness and the beauty of well-designed products. The best-known work of John Smith features two men (self-portraits of the artists) driving a car in a wide, rolling, southern landscape that has been borrowed from Hollywood films. The famous slogan HOLLYWOOD has also been borrowed from California, but in the painting it has metamorphosed into HOLOCAUST. In the context of present-day Estonia, ‘Holocaust’ has acquired a very dramatic meaning, since it is related to the accusations of Estonians’ supposed collaboration with Nazis.

positions; it proceeds only from the economic character of the product; it is always in time and in the right place; it uses modern colours, invests in espionage, and never does anything out of some internal urge or simply to fill time. Smith’s product is made immediately after the arrival of an order. It exists, like a parasite, only due to the already existing. He defines his effortless actions as jokes. His art is characterised by enchanting technical virtuosity, disinformation, craziness and the beauty of well-designed products. The best-known work of John Smith features two men (self-portraits of the artists) driving a car in a wide, rolling, southern landscape that has been borrowed from Hollywood films. The famous slogan HOLLYWOOD has also been borrowed from California, but in the painting it has metamorphosed into HOLOCAUST. In the context of present-day Estonia, ‘Holocaust’ has acquired a very dramatic meaning, since it is related to the accusations of Estonians’ supposed collaboration with Nazis.