A Collection of Repairs

When was the last time you repaired something? And what do you repair when you fix something?

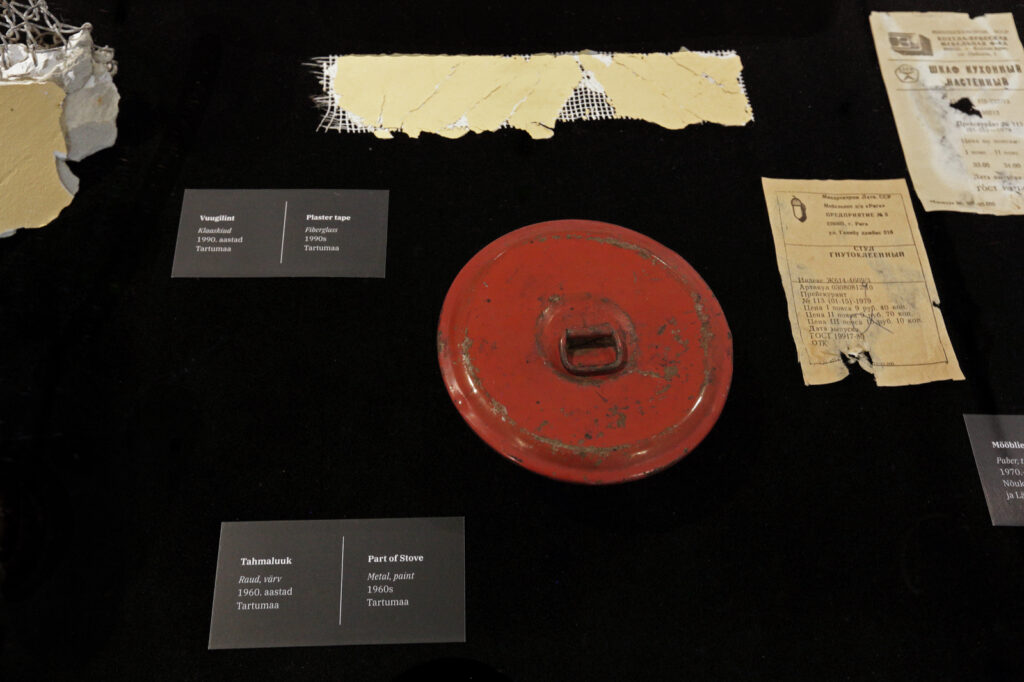

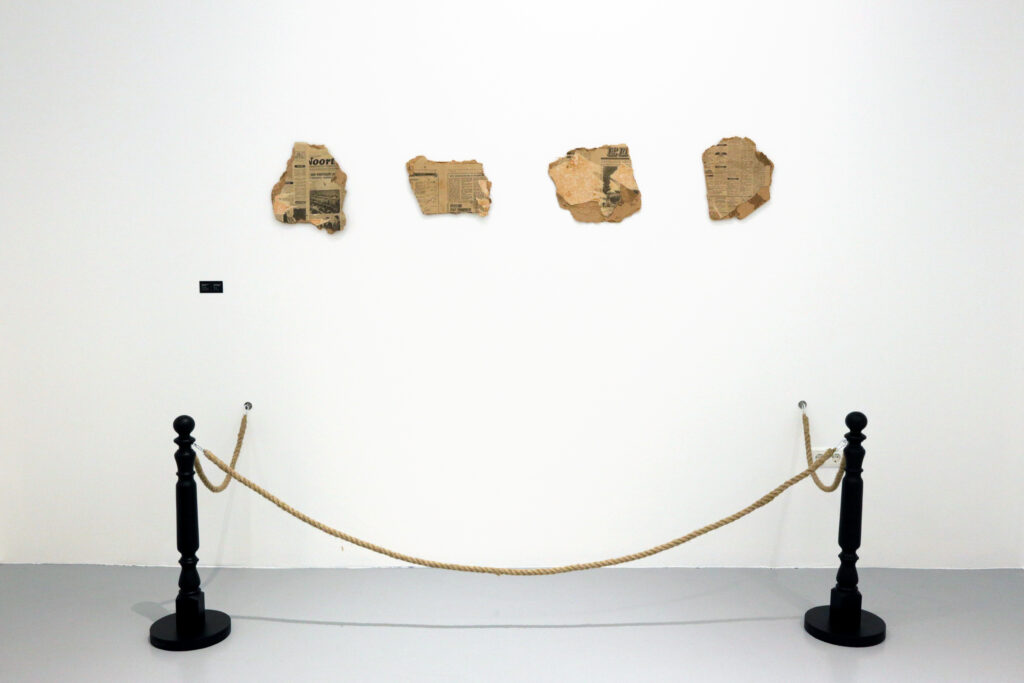

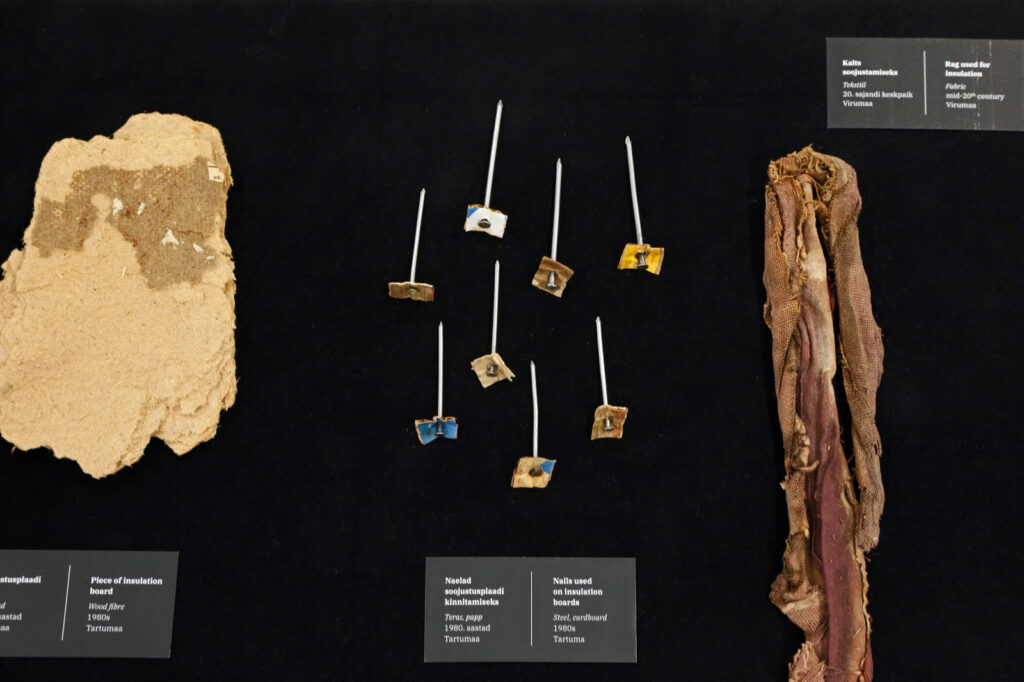

Over the last four years, Bita Razavi (Tehran, 1983) has been renovating an abandoned house in the Estonian countryside and an apartment in Tartu, documenting the mundane tasks done and also gathering different tools and traces that she encountered during the rebuilding process—as if it were an exercise in contemporary archaeology. Parts of a stove, furniture tags, tiles, nails, a leather drawer handle, repair tools, samplers of wallpapers, insulation fibre and board, mattress springs, a paint can, a drill, electric wires, old newspapers, a toilet seat cover and all sorts of unidentifiable things… “You are displaying trash and garbage”, said a visitor during the opening of Bita’s ‘Museum of Baltic Remont’ at the Kogo Gallery in Tartu (17 October – 16 November 2019: in June 2020, displayed at the Juhan Liiv museum).

The traces exhibited in the Museum of Baltic Remont talk of a time in which everyday life was an “object of constant improvement”—a society of remont.1 This is a museum of little things, of everyday remedies to the excesses of modernity, of the Russian byt’, of the shortage economy, of imaginary resourcefulness in the context of scarcity, of creating symbolic spaces of autonomy, corners of freedom and camaraderie.

Bita kindly invited me to visit the exhibition and discuss repair from an anthropological perspective. Bita then explained her fascination with the various materials that have been used to refurbish homes in the Baltic region throughout years of changing economic and political contexts. In the exhibition, she specifically engages with materials that were used during the Soviet era to insulate and renovate these kinds of country houses, presenting the materials as if they were samples for an ethnographic study.

The pieces of wallpaper and the variegated array of leftovers appear as maps that give access to a past future. We encounter the corpse of belonging and also of unrooting, of multiple attachments to places and to people, like a dissected cartography, leaving emotional veins and arteries open. Nowadays, however, we live in an era of material abundance and excess of things, of digital networks, and in some cases, of poverty of imagination and detachment from life cycles.

This exhibition is also a declaration of necessity after the succession of rooting and unrooting processes on the part of the artist. Bita aimed at constructing a sense of community and, the best way she found to do so, was to rebuild a house and refurbish an apartment. It does not matter if she lacked the skills because she managed to make friends along the way, working with them and with neighbors. For example, one neighbor told her that he could help build the stove in exchange for two of her artworks; Bita replied that it sounded like a great idea but quite probably he won’t like to have her artworks hanging on the walls of his house. This was because her art is not made to be nice, but to build something bigger and transcendental: call it home, family, legacy, care or community.

Then Bita confessed that: “No one has ever bought any of my works, which is something I ponder on, and at the same time I am proud of it; as if my works were not made to be sellable. None of my works have ever left me. And my new works are a house and an apartment, which could not be part of the collection of any museum as such”, while acknowledging that no museum or gallery has bought any of her works yet. However, in the last few months, three of her works have been acquired by two international institutions…

Heritage in the Making

By now you might have noticed that Bita is not the only maker of her art. She leaves room for other agents to step in, other people, other natural forces and elements, the work of time, the work of failure, the work of tools and micro-organisms: But why was a piece of underwear hidden between the layers of the wall in The Yellow House? And what does it tell about the previous owners and also about our identity as bricoleurs?

Bita’s Museum of Baltic Remont is not simply informed by remont, but informative about it, showing how it takes place within traditional structures and matter. This artist demonstrates that a careful observation of decay and the embodied engagement with mutable things might be an original form of storytelling.

For her, to work with her hands is a form of resting and of rehearsing hospitality. Indeed, hospitality is a key trope in Bita’s work: “I was born in Tehran, and what I like the most in Iranian culture is the notion of hospitality. My home is always prepared for guests. I don’t receive many guests after all, but I am always ready to host visits. I have noticed that even when I engage in repairs, I look at it from the eyes of possible visitors … I grew up in Iran during the Iran-Iraq war, and back then there was the feeling of living in a closed society, and an overwhelming sense of limits—of resources, materials, tools, knowledge… and also the movies and music we listen to. Then the borders slowly opened up. Something similar has happened in Estonia, from the Soviet time to the present. This has resulted in different generations having different relations to things, and also a sense of vanishing, that something is disappearing. I am personally influenced by this idea of crossing borders, and also by the aesthetics of vanishing”.

Identity and community are critical tropes in Bita’s work. For instance, in 2011, she prepared a video installation showing her performative marriage with Jaakko Karhunen at the Finnish Academy of Fine Arts. Alongside the video-documentation, she provided the legal documents of the marriage and a certificate applying for Finnish residency (indeed, this was a key part of both the logical motivation behind the performance and its potential critique). Bita is interested in how identities are formed by both legal documents and objects, paying attention to the performances, rituals, enactments that they—objects and legal requirements—correspondingly generate.

Another example is her work ‘An Observation on Inhabitants of a Utopia’, based on Bita’s experience as a cleaner in different apartments of Helsinki, noticing that Iittala designs are placed to demonstrate or perform Finnish identity. Also, in ‘Pictures from Our Future, Pictures from Our Past’, she engages with the current attitudes to newcomers in Estonia, with a photo series triggered by a comment heard by Bita in Tartu: “This is what our future looks like”, while pointing at her.

Museum collections are made up of items that come from the past and are assembled with the intention of producing a whole that is larger than its parts.2

In this case, however, the Museum of Baltic Remont collection is composed of something closer to ephemeral art, a quasi-technical set of elements produced in the present and with a limited lifespan. Bita’s collection is a form of documentation in progress, a particular point of entry into the making of things, a knot through which to explore the aesthetic relationality of things, materialising openings and closures in a larger network. Often, collections are considered as a home for objects, but in Bita’s case, the collection of repairs is rather a medium—for hospitality, for knowledge-making, for political concern. Her work appears then as heritage in the making,3 a sort of preservation without permission.4

Ecologies of Care

When listening to Bita talking of cohabitation and accommodation, it seems, however, that the object of work is the artist herself, and the Museum of Remont a material portrait of her landing in Estonia. There is indeed a sense of melancholy in her work, one which reminds one of the Georgian artist Nino Kvrivishvili’s installation ‘Searching for Traces’. Nino tells the stories of weavers and their families in Gori, making visible how networks of memories are formed through a series of objects, in some cases capturing involuntary retrospection and recovering thoughts and ideas that remained unacknowledged for a long time by rescuing neglected objects.5

In this sense, repairing cannot simply be reduced to utilitarian purposes, but also fulfils a symbolic ability for recuperating the self, healing the alienating breach of late-modernity and inter-generational ruptures and asynchrony. This was also shown, for instance, by Estonian artist Flo Kasearu, who after regaining a family house (albeit in a dilapidated condition) on the basis of the post-Soviet restitution law, decided to renovate it and transform it into the Flo Kasearu’s House Museum (FKM). Different kinds of artworks form the FKM collection: film, sculpture, ready- mades, performance, installations, drawings, rental ads—all playfully arranged.

To repair is, therefore, to connect: times, people, things. This is the key message, indeed, of artist Kader Attia, who has been practicing repair as a form of cross- cultural addition, re-appropriation and translation. Yet in its conceptual form, repair can be considered not just as therapeutic, in the sense of recovery and healing, but also political: making visible, activating, bringing to the fore, keeping people busy, as shown in the exhibition ‘Aesthetics of Repair in Contemporary Georgia’ that I organized with Marika Agu (TartMus 2016).

Discussions of repair are particularly relevant in Estonia; in this country, remains of the Soviet past were reduced to zero-value, to waste, and yet they are still crucial to understand the present, and are being rediscovered by a new younger generation.6 While taking care of things, and of people, we are being political, coming to terms with matter and with our surroundings, engaging in acts that go back on ourselves, bringing about transformative knowledge, intervening in the world, liberating negativism.

Repairing is part of the cultivation of care. As Bita’s work reminds us, the enactment of care is a matter of everyday interactions.7 However, as in the case of the labour of care, repair work has been overlooked in modern societies, as it favours persistence, attentiveness and accumulation instead of heroic acts of innovation. As a result, caregivers and maintenance workers have been too often left themselves without care and support.8

Bita does fixing and refurbishing as if it were a ceremony of renewal and healing, making community, practicing hospitality—as a hands-on mode of ethical agency that help us establishing stability in a broken world and to deal with the coming apart of things. In the Museum of Baltic Remont, we encounter Bita’s inner layers too; they are exposed, paradoxically, through what is removed, disposed and ephemeral. We are talking of a crafting existence, of the ordinary affects of repair, and of material sensitivity.9

Life is then presented as a constant process of creating a home away from home, negotiating and generating further mixed traces—which remain together in the form of unstable equilibria; as our fragile world does too.

1 Gerasimova, Ekaterina, and Sofia Chuikina. 2009. ‘The Repair Society’. Russian Studies in History 48 (1): 58–74, p. 59.

2 Pearce, Susan 1992. Museums, Objects, and Collections. Leicester: Leicester University Press. Martínez, Francisco 2019b. ‘The inertia of collections. Changes against the grain in the Rosenlew Museum if Pori, Finland’. Museum Worlds 7: 23–44.

3 DeSilvey, Caitlin 2006. ‘Observed decay: Telling stories with mutable things’. Journal of Material Culture 11 (3): 318–38.

4 Brand, Steward 2012. ‘Preservation without Permission: the Paris Urban eXperiment’. Introduction to the Long Now Seminar, November 13. http://longnow.org/seminars/ 02012/nov/13/preservation-without- permission-paris-urban-experiment

5 Grossman, Alyssa 2015. ‘Forgotten domestic objects. Capturing involuntary memories in post-Communist Bucharest’. Home Cultures 12 (3): 291–310.

6 Martínez, Francisco 2018. Remains of the Soviet Past in Estonia. London: UCL Press. https://www.uclpress.co.uk/products/109623

7 Fisher, B. and J. Tronto (1990) ‘Toward a feminist theory of caring’, in E.K. Abel and M.K. Nelson (eds.) Circles of Care: Work and Identity in Women’s Lives. New York: SUNY Press.

8 Mattern, Shannon 2018. “Maintenance and Care.” Places https://placesjournal.org/article/ maintenance-and-care/

9 Martínez, Francisco 2017. ‘The Ordinary Affects of Repair’. Eurozine 16 March, https://www.eurozine.com/the-ordinary- affects-of-repair/

- Photo by Kiur Kaasik

- Bita Razavi. Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi

- Bita Razavi. Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi

- Video still. Bita Razavi. The Essential Guide to Remont. 2019. HD video, B&W, sound, duration 8′ 35”, original language Estonian

- Bita Razavi. Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi

- Bita Razavi. Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi

- Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi

- Bita Razavi. Museum of Baltic Remont. 2019. Installation, dimensions variable. Installation view at Kogo gallery. Photo Bita Razavi