Estonian, Latvian and Lithuanian Design Exhibitions from the Early 1960s to the Late 1980s

During the Soviet years, joint Baltic exhibitions of furniture, posters, package design and the food industry, trademarks and logos, souvenirs and light industry, as well as fashion and jewelry from the three republics were frequently organized. Exhibitions shaped certain traditions and usually toured all three capitals: Vilnius, Riga and Tallinn. They also encouraged personal encounters between designers.

I have mentioned the very different spheres of objects and activities that nowadays have some relationship to design discourse. Looking at the titles of exhibitions from the early 1960s and 1970s, we don’t come across the English-derived term “design”. Back then, “dizain” had not yet become a buzzword, even though professionals knew and used the word. To gain a better understanding of this period, it is useful to know different keywords, such as “artistic construction”, “technical aesthetics”, “industrial modeling”, “economic achievements”, “household objects” and, as Viktor Buchly noted, “byt reform”.

Design was a field that emerged between industrial production and applied art, between machinery and aesthetics, characterized by the contradictions between unique projects and manufacturing defects, between professional mastery and simple hackwork, and between declared prosperity and perpetual shortage. Having chosen the sphere of exhibitions we more often encounter such qualities as uniqueness and modernity, and many kinds of declarations. I have chosen the brightest sparks from the different exhibitions, encounters and design projects, which provide a few insights and comparisons between Estonian and Lithuanian design[ii].

Baltic Design via Moscow: Exhibitions of Achievements and Export Shows

Special occasions of note were the export shows. Baltic designers participated in a dozen international USSR exhibitions with modern display projects where they presented unique design objects created exclusively for export shows: spatial installations, new furniture items, fashion design collections, modern home appliances, souvenirs and graphic design examples. In most cases, they were shown at trade shows and fairs featuring achievements in declared prosperity and propaganda themes.

Participation in exhibitions abroad enabled designers to realize their artistic ambitions, to get good commissions, to go beyond the borders of the Soviet empire and even the Iron Curtain, to obtain otherwise unavailable information, and to gain significant inspiration. Although the design projects tailored to trade shows, in most cases, remained unknown in the local context, such trips often led to creative breakthroughs and sometimes fueled the design field at home.

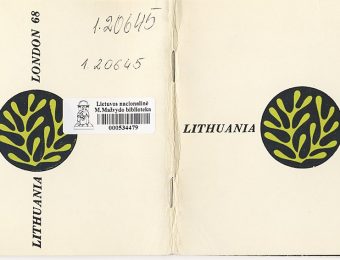

The first Soviet export exhibition where Lithuanian and Estonians designers met was in 1966. Lithuania and Estonia had their individual sections at the 1966 Leipzig Spring Fair, but there was a special Baltic focus in 1968 at the Soviet Union Industry and Trade Exhibition in London. Although it was one of the USSR’s propaganda-infused events in the West at the height of the Cold War, artistic and industrial products displayed many signs of modern national culture. Each Baltic Republic had its own pavilion of 500 square meters.

The Soviet Union Industry and Trade Exhibition opened on August 6, 1968 and lasted three weeks in one of London’s largest exhibition centers at the time, the now legendary Earls Court.[iii]

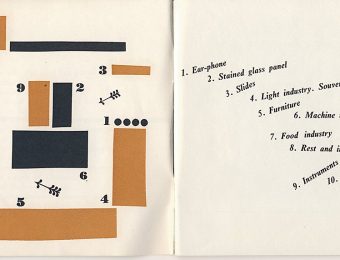

The show featured around 8,000 exhibits, which represented the Soviet achievements in science, industry, technology, art and culture, with a tribute to the space race showing such objects as Vostok, Sputnik, Venera-3, as well as an actual spacecraft cabin. In London, Lithuanians were praised for their machinery, innovative medical equipment, modern furniture, a kinetic stained glass installation by Algimantas Stoškus, and a graphically bold catalog designed by Antanas Kazakauskas.

Among 325 Soviet delegation members, there were 14 from Lithuania, 12 from Estonia and 11 from Latvia, as well as about 10 young women from the Baltics among the 21 representing the Fashion Design Bureau. Tadas Baginskas (b. 1936), the designer of the Lithuanian pavilion who had personally come to London to install the exhibition objects, recalled five decades later that it was the journey of a lifetime: “we had always looked up to the West and had a keen interest in Scandinavian, Italian and Japanese design. We did not consider the occupiers to be authorities on design. The most pleasing thing was that everyone noticed that at the London exhibition. Our exposition integrated perfectly.” And in this context, I would like to quote Michael Idov, who said that “the Baltic republics, closer to the edge of the Iron Curtain, were known to produce better made, sexier, and consequently more expensive products than their eastern Soviet counterparts.”

The Baltic artists who in 1968 enjoyed an opportunity to venture beyond the Iron Curtain for a month recall not only London’s vibrant urban life and arts scene, but also an unexpected development in the exhibition in its very last days. In late August, Soviet tanks invaded Prague, and calls for shutting down the exhibition altogether were voiced during protests in London. Due to these circumstances, and the fact that it was dedicated to a display of exports, the Baltic pavilions did not receive proper acclaim at the time.

Friendships and the Sparks of Competition

The London ’68 exhibition is also a good example of the creative friendships among Lithuanian and Estonian designers, particularly between Tadas Baginskas and the renowned Estonian designer Vello Asi (1927–2016). The Estonian pavilion for the London exhibition was designed by Eha Reitel and Kärt Voogre, but after a change of location and construction-related challenges, Vello was called to London to help.

Tadas and Vello first met in 1960 in Vilnius when they set up a joint exhibition of furniture from the three Baltic States in Vingis Park. The exhibition was organized on the initiative of the Experimental Furniture Design Bureau, established in Vilnius in 1957. The Lithuanian furniture exposition was designed and installed by Baginskas. It was his debut as an exhibition designer and the first “lesson in design composition” that he received from Vello Asi. They met again a few years later in Riga and became even closer friends.

In August 1968 they spent a month in London and according to the interviews with Baginskas[iv], they were impressed by the vibrant daily life and artistic atmosphere. They visited the Henry Moore vernisage, attended a private reception organized by Sir Paul Reilly (1912–1990), the head of the British Council of Industrial Design, and genuinely admired his hippie-style orange jacket and his dog Tapio, named in honor of his close friend, the Finnish designer Tapio Wirkkala (1915–1985), and they selected a new briefcase for Asi, who had to use a large portion of his pay for the London exhibition to buy the briefcase, but it served him well for a long time.

Despite the fact that most of the encounters resulted from the shared role of designers on professional assignments, either as members of teams of official representative exhibitions (representing either Estonia or Lithuania) or, more rarely, on personal initiatives, they were inevitably accompanied by a sense of competition. The exhibitions always highlighted certain novelties, the achievements of some and the shortcomings of others. More often, however, comparisons arising from cultural competitions were made between the two Baltic republics: which of them was the more modern, and whose artistic level and technical realization were higher. In some cases, these sparks inspired further creative searches and processes.

For instance, at the very beginning of the interview on Estonian and Lithuanian design, Baginskas readily admitted that Estonians were the main competitors of Lithuanian furniture designers at pan-Soviet and joint exhibitions involving the Baltic countries, although Lithuanians were sometimes ahead of them. At the same time, Lithuanian designers always emphasized that the Estonians were unmatched in the field of art design.

Estonian Art Design in the 1980s

In Spring 1987, two Estonian art design exhibitions were held in Vilnius, and there the word design was used intentionally. The first, held in the main exhibition hall (currently the Contemporary Art Center, CAC), introduced the works of six young Estonian designers and applied artists, with the very conceptual approach of the exhibition design led by Jüri Kermik. The second exhibition, which lasted only five days, brought to Vilnius the newest works of Eero Jürgenson, Toivo Raidmets and Leonardo Meigas, with the performative opening at the exhibition center in Lazdynai.

The Lithuanian press emphasized that the Estonians were unrivaled in the field of art design:

“Estonia is way ahead of us in terms of the development and popularization of design. … Estonian artists have become especially famous for their development of art design. This is design that creates new impulses for the development of industrial design and helps blaze new trails in the field of artistic construction.”

The Estonian architecture and design critic Mart Kalm, who came to Vilnius in 1987, also felt the need to make comparisons, this time complementing the Lithuanians. In Vilnius, Kalm was fascinated by the post-modernist interior of the Hotel Astorija, which he called the Lithuanian interpretation of Michael Graves, with rudiments of Pop Art, mentioning that “nothing like that has been created in Estonia!” The Hotel Astorija was a 1983 project by the architect Algimantas Šarauskas (b. 1952) in cooperation with the designer Jonas Gerulaitis (b. 1953), who designed impressive furniture in the style of the Memphis Group for the hotel restaurant and bar.

Neon, Jazz, Musical Protests and the Baltic Way

I would like to describe in more detail a few Estonian projects from the late 1980s. For the 1987 Vilnius exhibition, the designer Jüri Kermik displayed a sculptural group of lights, the “Holy Men of Vilnius”, created specifically for this exhibition. As the designer himself has explained, he created these light objects of impressive dimensions and forms by drawing inspiration from the history and architecture of Vilnius and the aura of the city itself, as well as things he had read about the city. While installing the design objects in Vilnius, Kermik included a soundtrack: in the corner of the exhibition hall, a tape recorder played jazz music specifically recorded for the Tallinn design exhibition.

The next year there was another Estonian project in Vilnius related to light design and music. It was a music shop window of vinyl records, designed by the Estonian artists P. Sisask, K. Jüriado and T. Suchis. It was part of the 1988 international competition, Golden Autumn, and won a prize for the most beautiful project. Looking at the white bust of a mannequin with a neon microphone placed against a background of curving lines and interrupted circles of colorful organic glass, it is important to keep in mind the actual socio-political context. The shop window design competition was organized as part of the International Congress of Advertising, which, as declared by the press at the time, “brought together around 500 participants: representatives of domestic and foreign trade, industry, tourism and airline companies from the entire Soviet Union, as well as Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia, Mongolia, Hungary and the German DR”. The 170 artists and designers created vibrant decorations for 63 shop windows on the central streets of Vilnius.

However, the shops shelves were becoming emptier and emptier, and consumer goods could only be bought using ration coupons. To illustrate the contradictions that emerged in the crumbling socialist system of the final years of the decade and the failing communist regimes, one of the songs of the time fits perfectly. It is the song “Funkcionieriai” (“Functionaries”) by the most famous rock group of the time, ANTIS. The rock band of Kaunas architects was formed in 1984 by the architect Algirdas Kaušpėdas (b. 1953).

Functionaries? Functionaries!

Functionaries – portfolio pilots!

[…]

Functionaries – buckish little men,

Tie pedants, suit cavaliers.

[…]

Faithful adherents of goods deficiency

Functionaries – miserable people,

[…]

What else could be the opinion?

Who says what the society needs?

[…]

If only nothing happened,

And Moscow, Moscow wouldn’t hear of it, –

Functionaries, start to tremble!

We support democracy with our hearts and minds[v].

This is not a direct illustration of the situation, nor is it a song about design functionaries, with the lyrics mocking “Soviet comrades” in general. And while researching the Soviet archives of export exhibitions we could imagine the methods, faces and the whole bureaucratic system of Moscow and the local functionaries of the time. What is more important here is the performative character of design projects and the context of protest, national rebirth and the Sąjūdis (the Lithuanian analogue of the Estonian Rahvarinne), which was an inseparable part of the late 1980s.

I would like to end this text with a recollection of one of the graduates of the Estonian State Art Institute, the interior designer Gintaras Lukoševičius, on how he and Eero Jürgenson participated in the tenth Gaudeamus, the Song and Dance Celebration of Baltic Students, in Vilnius in the summer of 1988, and how they carried the Lithuanian and Estonian national flags for the very first time.

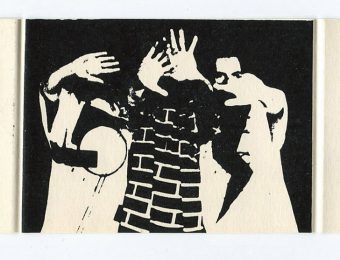

A year later, on 23 August 1989 – the 50th anniversary of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which had annihilated the sovereignty of the Baltic States – the people of all three Baltic States joined hands to form an unbroken human chain from Vilnius to Tallinn. As an illustration of the Baltic Way, I have chosen a poster by Jokūbas Zovė, Skoroshivatel Folder N. 1940, which won the 1988 political poster competition and a citation from the “March of Rock”, where Estonian and Latvian bands also actively performed: “Sąjūdis was a step forward, taken from a desperate pit. … In Lithuania people finally took responsibility: the first group because they were not afraid anymore, the others because they had started to tremble.”

Bibliography

Buchly, Khrushchev, Modernism, and the Fight against “Petit-bourgeois” Consciousness in the Soviet Home, Journal of Design History, Vol. 10, No 2, 1997, p. 161-176.

Idov, Made in Russia: Unsung Icons of Soviet Design, ed. Michael Idov, New York: Rizzoli, 2011.

Jakaitė, The Lithuanian Pavilion at the 1968 London Exhibition, translated by Jurij Dobriakov, Art in Translation, Vol. 7, 2015, Issue 4, p. 520-551.

Kalmas, Interjero dizainas, Literatūra ir menas, 11 July 1987, p. 3.

Tiškutė, Dizainas iš Estijos, Vakarinės naujienos, 6 May 1987, p. 1.

[i] This article is part of the postdoctoral research project “Lithuanian Design at International and Baltic Exhibitions 1966-1985: Origins, Influences, Tensions and Identities” by Karolina Jakaitė (Vilnius Academy of Arts), funded by the European Social Fund under act No 09.3.3-LMT-K-712, “Development of Competences of Scientists, other Researchers and Students through Practical Research Activities”.

[ii] I would like to thank Jüri Kermik and Kai Lobjakas, as the research on Lithuanian and Estonian design connections was related to the book New Pain: Young Estonian design of the 1980s, Tallinn: Estonian Museum of Applied Art, 2018. Also I want to thank the following Lithuanian designers and design researchers for their interviews, photos and the threads unraveled in this text: Tadas Baginskas, Rasa Balaišė, Jonas Gerulaitis, Kazimieras Januta, Lolita Jablonskienė, Rasa Janulevičiūtė, Vytautas Kibildis, Gintaras Lukoševičius, Darius Pocevičius, Albinas Purys and Algimantas Šarauskas.

[iii] It operated in the Kensington District between 1937 and 2017, when the entire complex was demolished.

[iv] Interview with T. Baginskas by K. Jakaitė and A. Kurg, Vilnius, 6 December 2010. This was my first interview with Baginskas, which led to subsequent discussions about Vello Asi, design in the Soviet era, connections between Lithuanian and Estonian designers, and various experiments and projects. Among the newest interviews was the video interview with T. Baginskas by K. Jakaitė, Š. Šlektavičius and G. Žemaitytė (Vilnius, 12 February 2016, from the archive of “Design Foundation” (www.dizainofondas.lt)

[v] Antis, Funkcionieriai, 1988, music P. Ubartas, lyrics A. Kaušpėdas (author’s translation), in: A. Kaušpėdas, Antiška, Vilnius: Tyto alba, 2013, p. 103.

The article is illustrated with pictures from the Lithuanian Central State Archives, the Russian State Archive of the Economy and the personal archives of designers.