If post-internet were a fairy tale character, she wouldn’t be the prettiest princess on Earth, loved by everyone. Nope, post-internet would be the evil godmother who would spend her days staring into the mirror, taking selfies and fancying herself. Post-internet is trivial, it’s vain, it’s arrogant…post-internet is so bad.

Does anyone still remember the ninth Berlin Biennale (of 2016)? Or is it already hidden on page 2 of Google Search? It was the manifesto of post-internet. Or its death notice, as some have said. Curated by the ‘highfalutin fashion collective’ DIS, the Berlin Biennale put art to shame, according to some critics. Or, as Dorian Batycka stated in Hyperallergic, DIS “seems more concerned with /…/ looking cool in Slavoj Zizek t-shirts than in curating anything that could remotely be considered a serious, relevant, or important exhibition of contemporary art.” So bad! The opponents of post-internet art have indeed said it is not anti-capitalist enough, not relevant enough, not something they think art should be. What, then, would post-internet fashion be like? Well, fashion never states its purpose would be something more than looking cool in a Slavoj Zizek t-shirt. Fashion is by definition superficial and foolish. It’s fickle and senseless, and that is exactly why it so unbearably perfectly describes the world we live in today.

Post-internet art asks us: what should art be after the internet? After the endless cat pics and millions of memes have clogged up our visual senses entirely? The question for fashion after the internet is similar. What is fashion after blogs, after the Kardashians, after Snapchat, with the always accelerating fashion industry and the fact that even fashion has become unfashionable (yes, high-end trend forecaster Li Edelkoort really said that)? What is fashion in a post-truth society, where we don’t have a Kantian differentiation between real and unreal values any more, in an era where there is nothing left but bluff and hype? It’s the situation where in real life doesn’t mean anything anymore, but there are still humans with real feelings, emotions and loves.

Kristel Kuslapuu lookbook 2016.

Photo: Tony Ottosson

Printed Internet

Here we have Laivi Suurväli (Laivi) and Sandra Kosorotova, young fashion designers whose conscientious works are based on the idea of resisting overproduction and offering a moment of security for the wearer. Kosorotova’s exhibition “Care. Value. Power. Control” was driven by the lack of control and care in today’s world. People have tried to replace control and care with a range of spiritual teachings, diets, yoga lessons and other mind-body practices. Kosorotova’s Master’s thesis work at the Estonian Academy of Arts, “The Plaza Collection; Fashion Activism as Reaction to Hyper-Consumerism”, focused on uniting slow fashion and activism. The unisex clothing could also be used as a rally banner. Laivi has tackled the European migrant crises in her works: her exhibition at the Tartu Art Museum, “On Disappearing And For Vanishing”, attempted to emotionally portray the long journey of an immigrant on his way to public recognition.

What happens when the internet appears more real than real life? It seems that one way to deal with this question is just to print out the internet. Laivi printed the internet on her fabrics and exhibition walls at her solo exhibition “Poor Girl/Too Cool”. The designer Kristel Kuslapuu prints and knits the internet on her colourful knit works. For some time there has been a fashion magazine called ‘Slacker’ in Estonia, initiated for slackers, obviously. It’s a pointless magazine in every sense: it appears only in print, most of the magazine consists of super-expensive fashion shoots, but the mag itself is free and is published in Estonglish (probably an editorial decision). It’s not only the era and colourful aesthetics that make the magazine so post-internet, but also the slacking part. We are killing time on Facebook and Instagram, and on our stupid smart phones. Everyone hates us for that. It all comes back to the idea of printing out things that should have just stayed on the internet.

East of the West

Where can we hide in the age of internet transparency? When we are ruthlessly followed by all the cookies of the world? Of course, one possibility is to print out the internet as Slacker does and just bury it somewhere. But where can you hide from the world, which is threatened by both climate catastrophe and the Third World War? “Fashion will turn to the East,” I was told some years ago by the Russian fashion collector Alexandr Vassilyev, whose collector’s exhibitions have become the main blockbusters in the leading Estonian art museum, Kumu. And indeed, he was right. Whether it’s the manufacturers in China and India or the strengthening Muslim impact in Europe and the USA, or maybe the reaction of fashion intellectuals to the conservatives who are trying to also force nationalist style in culture. Or perhaps, just boredom with mainstream fashion? The key may also be seeking protection from the surveillance society. Or, in Hito Steyerl’s words: “How do people disappear in an age of total over-visibility?”.

Sandra Kos(s)orotova full look, 2016. Photo: Ken Oja

Fashion is turning us into real-life avatars, cyber warriors who are looking for the last protection from Big Brother, and according to the latest fashion of wearing mesh scarves and up-to-date capes. As Ingeborg Harms wrote in her article in the Texte Zur Kunst fashion issue, as it is a custom for the often parodical fashion world, it occasionally turns out even grotesque, especially when the body is “covered” by mesh fabric or 50 shades of nude. The body seems to be covered but is still sheer and uncensored. This can also be seen in the works of Laivi, who is experimenting with how nude she can go, to uncover the tensions between naked and dressed. Mesh-loving Estonian designer Crystal Rabbit designs lingerie and sportswear. The cyber warrior is introduced with the men’s collections by Kalle Aasmäe or Katja Adrikova’s collection “Superior Man”. The cyber warrior wearing mesh fabrics and nude colours must be in perfect physical shape. Only the strong and healthy survive in the world after the internet. In order to have some kind of reality check during the era of great anxiety, we go to the gym and do yoga, have protein smoothies and green juices. The epoch of Care. Control. Value. Power has begun.

It’s Not Slav, But Who Cares?

The impact and influence of the East can also be found even closer. The hearts of the hipsters of the West have been conquered by the Parisian design collective Vetements and Gosha Rubchinsky for some time now. They use the streets of 1990s Russia, normcore and Soviet symbols as inspiration. Even Vogue selected Eastern Europe as its 2017 Hot Travel Destination and Eastern Europe’s designers were announced Not Going Anywhere in 2017. Does Asian fashion still seem a little too far out and frightening for Western youth? If so, then we still have good old Eastern Europe: it’s close, but still exotic enough.

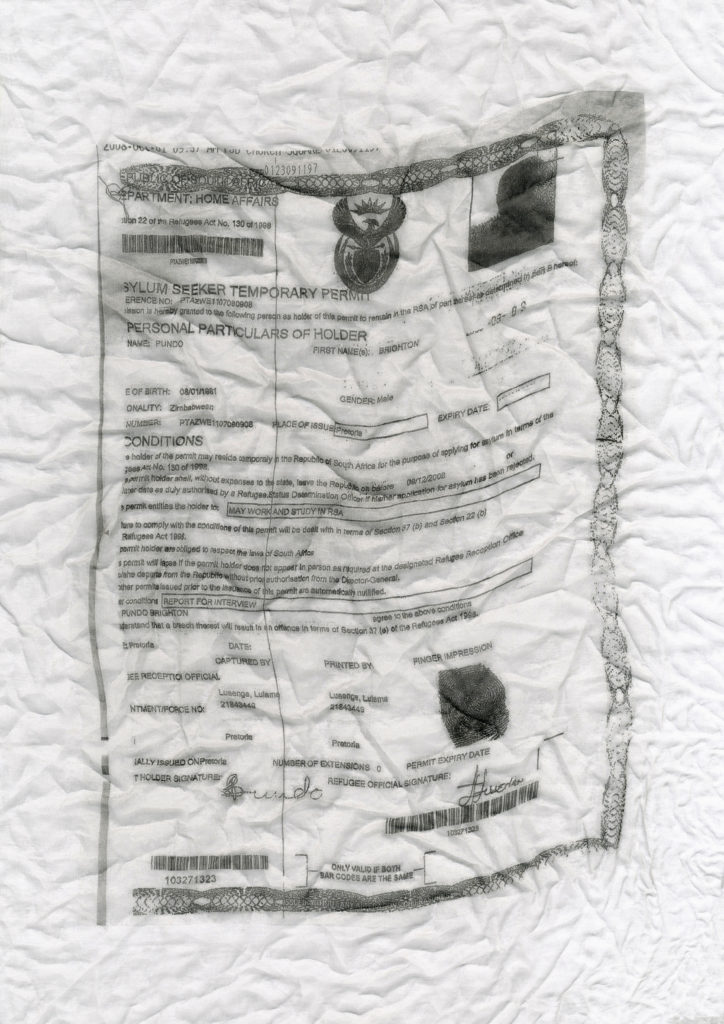

Laivi Suurväli “Temporary Permit”, 2016. Scan

In Estonia the trendy approach to the topic of the East of the West describes the new generation that are not ashamed of their Soviet past and not really nostalgic for it either. They remember the 1990s as a secure childhood (okay, someone was probably killed on your street but you were playing with Kinder Surprise toys then and watching German TV, so you probably didn’t notice). Baseball caps, sweatpants with huge logos, ugly jackets and slav squats have not quite made it to the catwalks but are present in the streets and popular culture. Just search on Instagram for “ossikükk” (Estonian for “slav squat”): people even use the pose in wedding pics! The Estonian rapper Tommy Cash sings with a Russian accent and mixes the internet with Slavic carpets. The designer Kristel Kuslapuu knits messages from the internet and popular culture into her cardigans. The poetics of 1990s thugs were brought back by Triin Ruumet’s film “The Days That Confused”, which won basically all the film prizes in Estonia in 2016. Estonians are not Slavs, but as one local Russian YouTuber, Life of Boris says: “who the fuck cares?” After all, we do have the jackpot: Slavic heritage and an even weirder thing called e-Estonia. If the apocalypse should come, Estonians can hide on the internet, which will be located in a Soviet blockhouse. That’s our post-internet survival kit.

*Header photo: Tommy Cash. Photo: Sohvi Viik